As congressional Democrats attempt to advance an ambitious agenda through a closely divided U.S. Senate, the filibuster has garnered renewed interest as a potential obstacle to legislation ranging from immigration and voting rights to overhauling the nation’s infrastructure. Often, a single senator can delay or block bills or other Senate business unless proponents can muster a supermajority of 60 votes. As a result, an increasing number of Democrats are calling for its outright elimination.

Last year, at the memorial service for American civil rights leader and Georgia congressman John Lewis, former President Barack Obama ’91, called the filibuster a “Jim Crow relic.” And while Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, the key swing vote on the Biden administration’s COVID-19 relief package, recently reiterated his opposition to jettisoning the filibuster altogether, the centrist Democrat from West Virginia opened the door to possible reforms.

But what exactly is the filibuster, how did it come to be such a powerful tool, and what does Jimmy Stewart have to do with it? For historical perspective, Harvard Law Today reached out via email to award-winning historian and legal scholar Kenneth Mack ’91, Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law and affiliate professor of history at Harvard University, and co-faculty leader of the Harvard Law School Program on Law and History.

Harvard Law Today: What is the filibuster? How did it originate?

Kenneth Mack: What we call the filibuster is simply an interpretation of the current Standing Rules of the Senate, primarily Rule 22 which governs Senate motions. It came about more or less by accident after 1806, when the Senate did away with a procedure that would have allowed debates to be terminated. The filibuster is essentially the attempt to prolong debate so that a bill, nomination or other Senate business cannot be brought to a vote. One of its principal uses in the nineteenth century was as a means of protecting the interests of slaveholders, while in the twentieth century its most prominent use was as a means of blocking civil rights legislation.

HLT: People often associate the term filibuster with someone talking for hours on end, but that doesn’t seem to be the case anymore. How has the rule evolved in recent history, and what have been some of the consequences?

Kenneth Mack ’91 is the inaugural Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law and affiliate professor of history at Harvard University, and co-faculty leader of the Harvard Law School Program on Law and History.

Mack: The filibuster is as much a product of the Senate’s norms and precedents as it is of the formal Senate rules. In the 1970s, the Senate lowered the required number of votes to end debate from 2/3 of the Senate to 3/5 (60 senators) and made other changes to keep a filibuster from stopping all Senate business, but that also helped lower the consequences of mounting a filibuster. This helped normalize the filibuster. More recently a norm has developed that allows one senator merely to signal that they will not consent to end debate — placing a “hold” — often by simply placing a phone call or sending an email. A senator can often do so without even publicly acknowledging it. The silent filibuster proliferated massively during Barack Obama’s presidency. The consequences have been both to empower the Senate majority leader, who needs to impose party uniformity to get anything done, and to allow individual senators to tie up the nation’s business, offer no explanation, and pay little or no political cost for doing so.

HLT: Why do some lawmakers see this as such an important piece of congressional history to retain? Why are others so fiercely opposed to it?

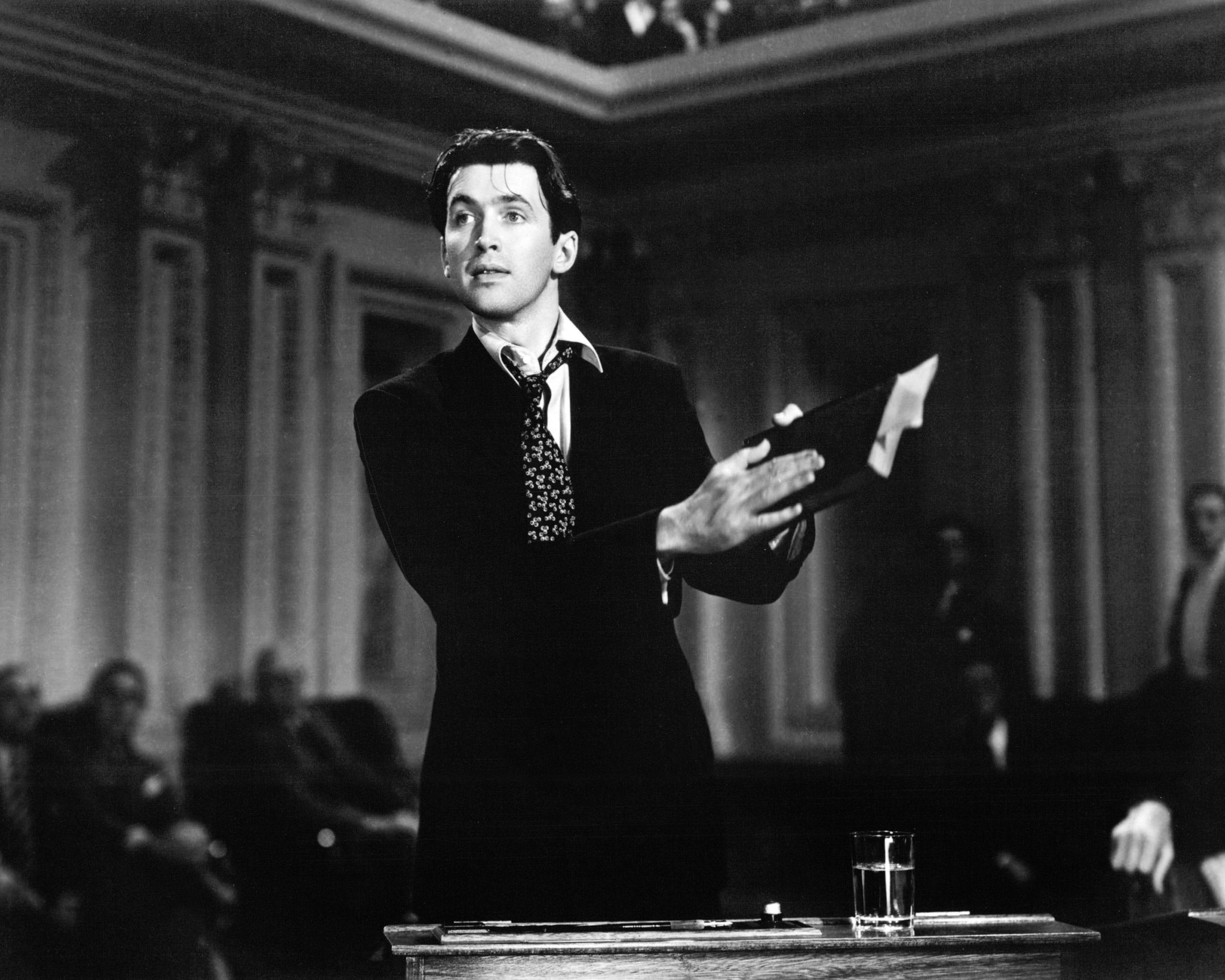

Mack: The modern filibuster was invented in the segregation era, but its current defenders assert that it protects the minority party’s interests and those of its voters. And of course, today’s majority might be a minority two years hence. The filibuster’s opponents point to the fact that with the normalization of the filibuster, there is now a 60-vote threshold even for much ordinary Senate business, and that this is not how the filibuster worked even in the era of “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.”

HLT: Last summer, during his remarks at John Lewis’ funeral, Barack Obama referred to the filibuster as “another Jim Crow relic,” suggesting that doing away with it would be one way to honor the legacy of the late civil rights activist. How is the filibuster related to Jim Crow laws? How was it used during the civil rights era?

Mack: Rep. John Lewis became famous as a young man for courting death and mob violence in his civil rights organizing, which contributed to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Georgia Senator Richard Russell and other segregationist senators were, in many ways, Lewis’ most powerful opponents. Russell helped to develop the modern filibuster, including the modernized version of Rule 22 in 1949, in order to ensure that civil rights bills could not pass the Senate. Although other types of bills sometimes garnered filibusters, civil rights measures were the only category of bills that were routinely blocked from passage by the filibuster.

HLT: Are there ways to reform it, short of getting rid of it altogether?

Mack: Congress can pass a law and specify that a particular kind of measure can’t be filibustered, as has been done with budget reconciliation. Congress can simply pass legislation under the pre-existing budget reconciliation process, such as is now being attempted for the COVID relief bill. The Senate can also change the filibuster by simply re-interpreting Rule 22 using a procedural maneuver that makes certain things immune from the 60-vote requirement, as it did using the “nuclear option” in 2013 and 2017 with regard to nominations. The Senate could also decide that it is not a “continuing body” and thus that its rules, including Rule 22, don’t carry over from one Congress to the next, which would permit a simple majority to write new rules when a new Congress convenes. There have been various proposals, including lowering the threshold for overcoming a filibuster to something less than 60 votes, allowing filibusters for only certain types of matters, or simply forcing filibustering senators to take the floor and debate openly, that combine some elements of the above.

HLT: Has the Senate changed the filibuster rule in the recent past and how has that worked out?

Mack: There have been two relatively recent changes, but neither has eliminated the underlying problem. The nuclear option has made it easier to confirm nominees but left the Senate as deadlocked as ever on other issues. The lowering of the threshold to 60 votes during the 1970s contributed, perversely, to the proliferation of filibusters. While rule changes can make a significant difference, part of the problem lies in the underlying norms of the Senate that promote secrecy, empower individual senators to act arbitrarily, and shield fundamentally anti-democratic actions from public scrutiny. It would be difficult to make headway against that, but some rule changes would be a good start.