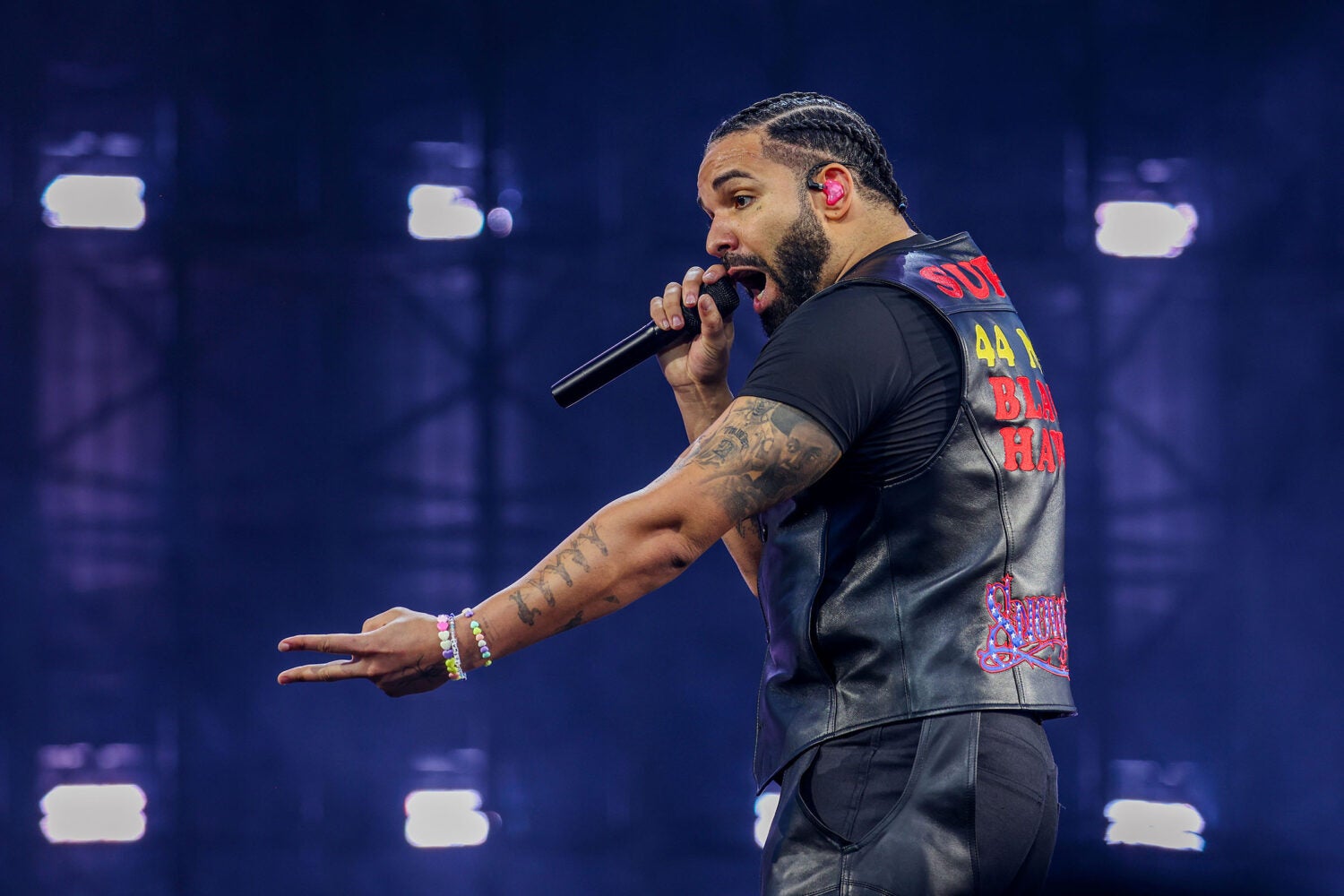

In a 2013 song, the musician Drake raps that he “started from the bottom, now we’re here.” But if “here” relates to the popularity of his music on major streaming platforms, that location might now be in contention, thanks to a new lawsuit filed against the Canadian entertainer.

In a class action suit filed in December, two Virginia residents allege that Drake, along with internet personality Adin Ross and another defendant, promoted an illegal online casino, then used profits from the scheme to artificially bolster play counts of Drake’s music on digital services such as Spotify. The defendants are facing a similar lawsuit filed in Missouri in the fall.

Drake, who is expected to drop a new album, “Iceman,” this year, has not yet commented on either case. In an October livestream, Ross used colorful words to describe what he viewed as the illegitimacy of the Missouri suit.

The allegations center on Drake’s extensive promotion of Stake.us, a “social casino” that enables customers to play games such as slots and poker with virtual currency. But the plaintiffs argue that the platform’s e-tokens are merely a stand-in for real dollars, which would make its activity illegal in Virginia and elsewhere in the U.S. Further, they claim that Drake and the other defendants used money earned from the site to hire bots and streaming farms to boost the artist’s play numbers on music platforms, “distort[ing] recommendation algorithms,” and violating state consumer protection law.

The suit also argues that, in working together to do these things, Drake and his codefendants violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), a law originally designed to tackle organized crime.

According to Duncan Levin, a lecturer at Harvard Law School, bringing RICO into a civil lawsuit “lets plaintiffs tell a bigger story.”

“Instead of focusing on one bad transaction, they’re saying the whole system was set up to make money in an illegal way,” he says.

Levin, a former assistant district attorney and federal prosecutor, is currently teaching a Winter Term course with Professor Ronald Sullivan called Cash, Crime, and the Constitution: The Legal Frontiers of Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering. He says that gambling law has historically been formalistic, crafted to address “in-person casinos and betting slips, not apps and virtual tokens.”

That framing has thus far allowed certain kinds of online gambling activity to go under- or unregulated, Levin adds, pointing to legal gray areas such Stake’s use of virtual money.

“What we’re seeing here really isn’t about Drake in isolation,” he says. “It’s about the legal system struggling to keep up with business models that sit just one step ahead of existing regulatory categories.”

The use of tokens or cryptocurrency can slow down the process of determining whether Stake.us ultimately does violate U.S. gambling laws, Levin says. But he warns that, if the site is operating illegally, it won’t outrun the law forever.

“I don’t think the law is fooled just because a platform uses something it calls ‘virtual tokens’ or ‘crypto’ instead of dollars,” he says. “No matter what the technology is, the judge is going to ask a simple question: Are people sending real money, and is the system designed so that real money predictably flows to the platform?”

In an interview with Harvard Law Today, Levin helped dissect the lawsuit against Drake — and shared why this complex case could be making “Headlines” for years to come.

Harvard Law Today: What are the main things the plaintiffs are alleging in this lawsuit?

Duncan Levin: At a high level, the lawsuit appears to rest on two interrelated theories. First, the plaintiffs allege an unlawful gambling enterprise, arguing that the online platform operated as a real-money casino disguised through the use of virtual tokens, in violation of state gambling laws. Second, they layer on a federal civil RICO theory, alleging that this gambling operation constituted an “enterprise” engaged in a pattern of racketeering activity, and that various defendants, including promoters, participated in or benefited from that enterprise. The complaint also appears to include consumer protection and unfair competition claims, particularly around deceptive promotion and inducement of users to spend money under allegedly false pretenses.

HLT: One of the first challenges the plaintiffs will face is getting certified as a class action by a court. Could you tell us how a court is going to think about that issue here?

Levin: Class certification may be one of the plaintiffs’ biggest hurdles. Gambling-related harms often vary widely among users: Some people lose significant sums, others lose very little, and some may even come out ahead. That variability can create problems for commonality, predominance, and damages models under Rule 23 [of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which govern civil lawsuits]. Courts are often skeptical of class actions where individualized questions of reliance, causation, or loss threaten to overwhelm common issues, even if there is a shared theory of wrongdoing.

HLT: Many people know RICO as a tool prosecutors used to target the mob in the 1970s-90s. How does RICO work in the context of a civil suit?

Levin: Civil RICO allows private plaintiffs to sue for treble damages if they can show injury to business or property caused by a pattern of racketeering activity conducted through an enterprise. While RICO was originally designed as a tool against organized crime, private civil RICO claims are not unusual, particularly in cases involving alleged fraud schemes. That said, courts scrutinize these claims closely. Plaintiffs must plead the enterprise, the racketeering acts, continuity, and causation with specificity, and many civil RICO cases are dismissed at the pleading stage for failure to meet those demanding standards.

HLT: Real-money online gambling is illegal in most U.S. states, including Virginia. But Stake uses virtual currency. How will a court evaluate if what the platform is doing is legal?

Levin: Courts tend to look past formal labels and examine economic reality. The key questions usually include whether users pay real money to participate, whether the tokens have real-world value or can be converted into something of value, and whether the platform meaningfully simulates traditional gambling mechanics. If the virtual currency functions as a proxy for cash, either directly or indirectly, courts may treat the activity as gambling even if the platform avoids explicit cash payouts.

HLT: Does Drake’s promotional role affect potential RICO liability differently than if he were an owner of the platform?

Levin: Yes. Ownership and promotion are treated differently, but promotion alone does not automatically insulate someone from liability. Under RICO, a person can be liable if they knowingly participate in the conduct of an enterprise’s affairs through racketeering activity. Plaintiffs would need to show more than mere endorsement; they would have to plausibly allege knowing participation or direction, or that the promotional activity itself furthered the alleged racketeering scheme. That is a fact-intensive inquiry and often a major battleground in motions to dismiss.

HLT: This case involves what feel like disparate claims — illegal gambling and consumer protection. Is it unusual for a civil lawsuit to combine these types of claims?

Levin: It’s not uncommon for plaintiffs to plead multiple theories arising from what they characterize as a single overarching scheme. RICO, in particular, invites this kind of aggregation because it focuses on patterns of activity rather than isolated acts. That said, courts will often test whether the different strands truly belong together or whether they are improperly bundled. If the claims are too attenuated from one another, a court may sever them or dismiss some while allowing others to proceed.

HLT: What must the plaintiffs ultimately show to win in this case?

Levin: For the gambling-related claims, plaintiffs must show that the platform constitutes illegal gambling under applicable state law and that they suffered legally cognizable losses as a result. For RICO, the bar is higher: they must establish the existence of an enterprise, a pattern of qualifying racketeering acts, continuity, and a direct causal link between the alleged racketeering and their financial injury. Each of those elements is independently demanding.

HLT: You mentioned that these types of lawsuits can drag on for a long time, mostly for procedural reasons. What factors influence whether this case will settle or ultimately go to trial?

Levin: Several forces tend to push cases like this toward early resolution if they survive motions to dismiss: litigation cost, reputational risk, regulatory overlap, and uncertainty around class certification. Conversely, defendants may choose to litigate aggressively if they believe the legal theories are overextended or vulnerable at the pleading or certification stage. Much depends on early judicial rulings, particularly on motions to dismiss and class certification, which often shape the entire trajectory of the case.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.