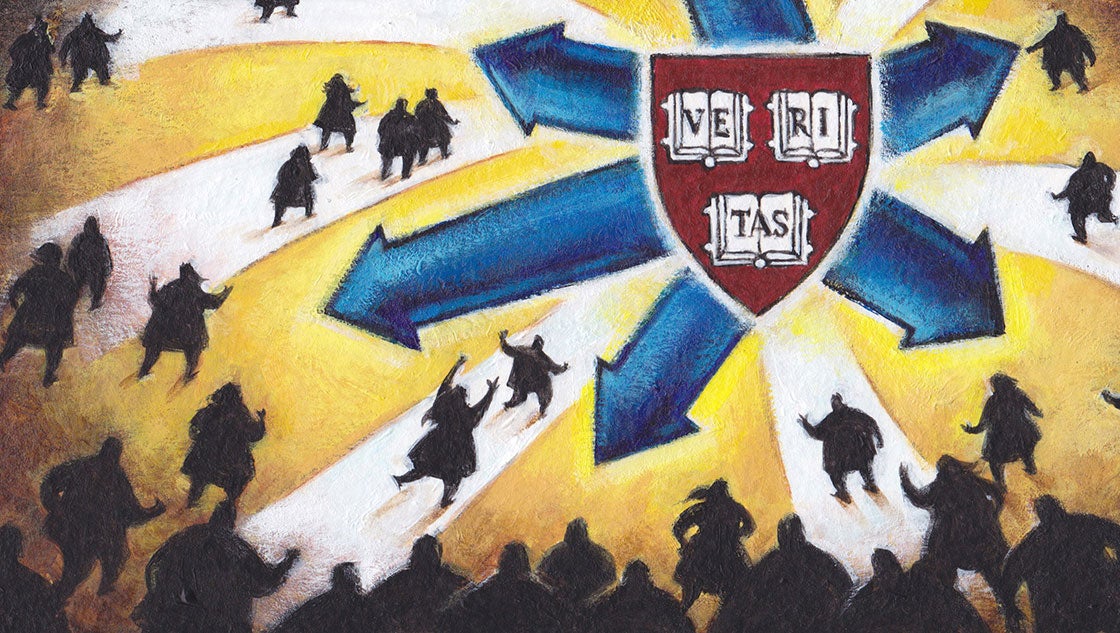

Programs work to aid individuals, opening vistas that many in struggling communities have never seen

This is the last in the Harvard Gazette’s series on inequality, one of America’s most vexing problems, examining Harvard’s ground-level efforts to make a difference in the surrounding communities, and beyond.

On a cold winter morning in 1848, Edward Everett, then president of Harvard, noticed a chilled freshman lacking an overcoat. According to the Annals of the Harvard Class of 1852, the freshman received $30 to buy a coat. Renamed the Winter Coat Fund, the program still exists and may be Harvard’s oldest effort to help the underprivileged. Some analysts of America’s deep schisms involving inequality say that large-scale solutions are needed to combat problems nationally. But others say that fundamental fixes can best begin locally, in communities, with programs that improve life neighborhood by neighborhood. Change the difficult conditions under which people struggle, they say, and you start to change their lives for the better.

[pull-content content=”

At Phillips Brooks House, we’re focused on community service, but we’re not only serving the community. We’re working with the community to make it better.

Jing Qiu ’16

A number of Harvard-based programs take that advice to heart, and some have done so for more than a century.

In 1904, a group of students founded the Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA) to honor a Harvard graduate and preacher who helped the poor. The student-run group now hosts 80 programs that involve a whopping 1,500 students in public and community service.

Various Harvard departments and Schools have long embraced efforts to help surrounding communities. The Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, for instance, has provided free legal representation to poor defendants since 1913.

Over time, the scope of University-affiliated programs has grown dramatically, along with their reach. They include free medical screenings through the Harvard Medical School (HMS) Family Van program in Dorchester, the tutoring and mentoring of Boston high school students through the Crimson Summer Academy, and efforts by Harvard-affiliated Partners In Health to fight Ebola in Sierra Leone, tuberculosis in Russia, and HIV in Haiti.

Other programs benefit nearby communities directly. The Ed Portal connects professors, students, and the University’s vast educational resources with residents of Allston and Brighton. A partnership with the nonprofit group Food For Free has provided more than 40,000 pounds of healthful food to local pantries.

Here are some examples of how local involvement can have a ripple effect in combatting inequality, person by person and case by case.

Harvard health van brings care to the community

Harvard Medical School’s Family Van reaches Boston’s underserved neighborhoods in the most direct way possible: by driving there. The van’s screening and referral services help bridge health inequalities by connecting local residents with a health care system that may otherwise seem distant and inaccessible.

Help with legal problems

Every year at Harvard Law School (HLS), 50 student attorneys help local residents with legal matters, from child custody to evictions to unemployment problems to Social Security benefits. The students do so through the Legal Aid Bureau, the nation’s oldest student-run organization offering free legal services to residents struggling to make ends meet. The students commit to at least 20 hours of work per week during two years, and handled 300 cases last year. The bureau, which is funded by Harvard, is the second-largest provider of free civic legal aid locally, after the nonprofit Greater Boston Legal Services.

“It’s really like having 50 full-time lawyers that Harvard is contributing to civic legal aid per year,” said Esme Caramello, clinical professor of law and the bureau’s deputy director.

The bureau strives to mirror the community it serves. The participating students select the next class of student lawyers, and they promote diversity because it encourages inclusion, said Amanda Morejon, current president of the bureau. Morejon graduated from the College in 2013 and will receive her degree from the Law School in May.

“We don’t want to be so far removed from our clients,” said Morejon. “Our clients are a racially and ethnically diverse population, all low-income. I had a client who was a Hispanic woman, and my being a Hispanic woman was extremely important to her.”

“The bureau is the most diverse organization at HLS,” said Caramello.

The community need is great, and sometimes exceeds the bureau’s capacity. “Three times a year we shut down the phones,” said Caramello. “We can’t take more cases.”

At HLS, other programs also offer free legal representation, including the Criminal Justice Institute, the Harvard Defenders, and the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, in which students represent refugees and asylum seekers.

From clothes to tutoring to shelter

For Jing Qiu ’16, president of the venerable Phillips Brooks House Association, the struggle for equality starts at home.

“We’re fighting inequality in Cambridge and Boston,” said Qiu at a café near Harvard Square. “At Phillips Brooks House, we’re focused on community service, but we’re not only serving the community. We’re working with the community to make it better.”

Inspired by the memory of the Rev. Phillips Brooks, a Harvard graduate who advocated social service, students founded the association to serve “the ideal of piety and charity and hospitality.” The association at first provided clothing and ran book drives and taught Harvard courses to local high school graduates, and it operated mainly in Cambridge.

Now the group offers programs through which students buddy up with Alzheimer’s patients in Roslindale or mentor recent immigrants and refugee youths in Dorchester or teach English in Chinatown. To help the homeless, the group also hosts a winter emergency shelter, a summer transitional shelter, and, most recently, a youth shelter. Students run the programs, which are funded by the University.

As president, Qiu oversees programming, operations, and staffing. “It’s more managerial than volunteering,” she said of her responsibility. “I have to do a lot of overseeing, but the work has inspired me to pursue a career in public service.”

Volunteering at PBHA helps students to see the effects of inequality on people’s lives, said Qiu.

“At least for me, volunteering is not an extracurricular activity,” she said. “It’s more than that. It’s a social responsibility. Inequity is structural, and through social service, we’re doing our part to level the playing field.”

Medical help from the Family Van

Ever since the Family Van began rolling on Martin Luther King Day in 1992, the Harvard Medical School program has helped to improve access to care and health resources in underserved communities.

The brainchild of Nancy Oriol, now dean for students, associate professor of anesthesia, and lecturer on social medicine at HMS, and then-medical student Cheryl Dorsey, the mobile clinic has treated more than 80,000 patients over the years. By providing curbside testing, free health screenings, and referrals for social services to residents of Dorchester, Roxbury, and East Boston, the van serves the “medically disenfranchised,” Oriol said. When it comes to health outcomes, she said, ZIP codes are better predictors of what’s needed than genetic codes.

“The disparities that exist are pervasive. They are all tangled. They are race, they are ethnicity, they are gender identification, they are ZIP code, they are education, they are employment. All of those things work together,” Oriol said. “Inequality of any sort, lack of opportunity of any sort, is harmful to your health. Lack of knowledge is harmful to your health.”

The mobile clinic also fosters trust between health care providers and the communities. Residents who might not go to a clinic are more comfortable knocking on the van’s door, even for questions unrelated to health, as happened when the daughter of a sex worker came in one day.

“She said, ‘Nobody in my world knows algebra; can you help?’” Oriol said. “And we did.”

Inside the van, health professionals handle blood pressure checks, HIV tests, family planning issues, and other services. The van also hosts HMS student interns, who get a taste of patient care and learn firsthand about the real-world pressures affecting patients.

[pull-content content=”

Inequality of any sort, lack of opportunity of any sort, is harmful to your health. Lack of knowledge is harmful to your health.

Nancy Oriol

Ishaan Desai ’15, who has volunteered with the van since 2014, said the experience allowed him to serve the community and see inequality close-up.

“From Cambridge to Roxbury or Dorchester, I realized that health disparities in the same metropolitan area are quite stark,” he said.

Rainelle Walker-White, who has worked with the van program for 22 years, agrees.

“It’s an opportunity for people who’d never get health care to walk into the Family Van to get the services that they so need, and that they deserve,” said Walker-White. “Going to the hospital sometimes is a barrier to people because they don’t have health insurance.”

The van is a rolling tutorial on health disparities. “We try to teach it in our schools,” Oriol said. “Medical schools understand that the social determinants of health are real, and if we ignore them we might as well be ignoring any major disease.”

Oriol, who is no longer involved in the van’s day-to-day operations, said that mobile clinics help to remove barriers to care, save money on emergency room costs, and improve residents’ health.

“It’s part of the community,” Oriol said. “It’s just a different part of the health care system.”

Climbing the economic and educational ladder

In 2001, Monica Tesoriero began working as a cashier at Harvard Business School’s cafeteria. She spoke little English. Now Tesoriero works at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, where she manages its overseas financial operations and faculty grants.

Tesoriero, who learned English, finished her GED, took computer classes, and earned a bachelor’s degree in social science through the Harvard Extension School, credits her progress to the Harvard Bridge Program, which offers training and education to the University’s entry-level workers.

“It was a bridge to a better life,” said Tesoriero at her office. “I didn’t want to be a cashier all my life. Thanks to the program, my life changed for the better.”

That’s what Carol Kolenik had in mind when she created the program in 1999. After coming back from a two-year stint in Vietnam teaching ESL teachers, Kolenik wanted to help workers to improve their lives. First, she taught English to 38 service employees at the Harvard Faculty Club. The program was a hit with workers and managers who realized the benefits of a trained workforce.

Now the program reaches 500 workers, from custodians to landscapers to parking attendants to contractor employees to postdoctoral fellows. Every semester, the Mount Auburn Street office hums with 53 classes, including TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) preparation, computer skills, and college prep. There are internship programs, mentoring and tutoring, and citizenship classes. About 200 workers have become U.S. citizens through the program. For Kolenik, the gains go beyond words or numbers.

“The best, biggest benefit is that it brings equity to all Harvard employees, from faculty to postdocs to service workers,” said Kolenik. “Basically, the people who wear uniforms and name tags are now being given … opportunities for education and professional development that historically were never afforded to them.”

With fresh skills, workers can earn promotions or new jobs within and outside the University. Kolenik beams with pride when she talks about an overnight custodian who became a bank teller, a dining-service employee who is now a student at Harvard Kennedy School, and a mailroom worker who is now in accounting.

For Tesoriero, the program sets a good example for other institutions to follow because it benefits both workers and employers.

“My life was turned around,” she said. “The University is smart in investing in people who are already working here and helping them discover they have other talents beyond making omelets.”

A portal to Harvard for Allston and Brighton

On any given day, the Harvard Ed Portal buzzes with activity. Inside the brick building with shiny glass doors at 224 Western Ave. in Allston, Harvard students mentor local schoolchildren, organizers run toddler and baby groups, and instructors offer programs on wellness, arts, science, education, and professional development. At night, professors give public lectures about history, science, and music.

The program is a partnership among Harvard, the city of Boston, the Harvard-Allston Task Force, and the Allston-Brighton community, and is part of the $43 million community benefits package associated with the University’s 10-year institutional master plan. Approved by the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 2013, the plan outlines Harvard’s expansion in Allston.

Assisting through the Financial Aid Initiative

Early in this century, as the gap between rich and poor Americans widened, Harvard officials grew concerned about whether the campus was properly addressing income inequality. A 2003 Century Foundation report had said that, in the Ivy League, Harvard had the second-lowest number of Pell Grant recipients, most of whom have financial need. The report showed that Harvard still resembled an elite institution, where low-income students were underrepresented by nearly 70 percent, as then-Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers noted.

That soon changed. A year later, Harvard launched the Harvard Financial Aid Initiative (HFAI), which opened the gates wider to low-income students by offering them full financial aid if their families made less than $40,000. Harvard made its income guidelines public, said Sally Donahue, director of financial aid, to better reach low-income students who did not know about Harvard, or who did not believe it was affordable for them. Fast-forward to 2016. The initiative now offers full financial aid to families earning below $65,000, and asks families with typical assets and incomes up to $150,000 to contribute from zero to 10 percent of their income. More than half of its students receive some form of financial aid, and one in five undergraduate families pay nothing. Since the launch of HFAI, Harvard has awarded nearly $1.5 billion in grant aid to undergrads.

[pull-content content=”

You can’t understand inequality unless you’ve lived it. When you talk to somebody who has lived it, you can understand how it affects people’s lives. We bring together people of different backgrounds, and diversity can be uncomfortable, but to me, that’s where learning begins.

Anya Bernstein Bassett

Much has changed since HFAI was created. Under President Drew Faust, financial aid has been a high priority. In 2007, she and Michael D. Smith, Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, built on the financial aid program by unveiling a similar initiative to help middle-income families. For fiscal year 2015, close to $174 million will be spent on undergraduate financial aid. Attending Harvard without aid costs about $65,000 per year, and by offering to provide full financial aid for families that can’t afford it, Harvard is able to keep its doors open to all students, regardless of their socio-economic backgrounds, said Donahue. The resulting socio-economic variety in the undergraduate experience — both in the classrooms and beyond — provides a broader and more stimulating education for students. In a world of increasing economic inequality, ensuring access to higher education for talented students has never been more critically important, Donahue said.

“Using our financial initiative to open our doors to all students, regardless of their socioeconomic backgrounds, is one of the most powerful ways of reducing inequality in our country and the world,” she said. “This is actually very powerful, because it’s providing a more diverse and multifaceted education, both in the classroom and outside, for all students.”

The shift also makes teaching a richer experience, said Anya Bernstein Bassett, dean of undergraduate studies and senior lecturer in social studies. Bassett teaches “Inequality and Social Mobility,” and having students from all walks of life brings in different perspectives and voices.

“You can’t understand inequality unless you’ve lived it,” said Bassett. “When you talk to somebody who has lived it, you can understand how it affects people’s lives. We bring together people of different backgrounds, and diversity can be uncomfortable, but to me, that’s where learning begins.”

Encouraging the young to aim higher

When Harvard unveiled its financial aid initiative in 2004, it also launched a program to help students get ready for college.

Targeting high-achieving ninth-graders at public schools in Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, the Crimson Summer Academy (CSA) is a three-summer program with courses on public speaking, writing, science and technology, and college preparation.

The students sleep in Harvard dorms during the week, attend lectures by Harvard faculty, and receive mentoring from Harvard students, all of which helps them to realize that the dream of attending college is attainable. It’s a dream that has come true for the 90 percent of Crimson graduates who over the past 12 years have completed college. They have gone off to prestigious universities across the country, a measure of the program’s success, says CSA director Maxine Rodburg.

“Many of these kids would have gone to college, but to less prestigious ones,” said Rodburg. “We helped them aim higher. We try to expand their sense of the possibilities because we feel they are entitled to the larger world that upper-middle-class kids take as a birthright.”

The students, who come from low-income families, are nominated by 36 high schools and follow a rigorous program to help them ace the application process and thrive in college.

For Crimson graduates Fatah Adan and Meyling Galvez, both now freshmen at Harvard, the academy provided a boost in academics, guidance on college applications, and a community of mentors and peers who offered key support.

“Without this program, I would definitely not be here,” said Adan, who grew up in Jamaica Plain, a child of Somali refugees. “Harvard is in our backyard, and many of us don’t think about Harvard.”

Galvez, a daughter of Guatemalan immigrants who attended a charter school in Boston, thought about Harvard but didn’t think it was possible to attend.

“My parents always pushed me to excel in school,” she said. “My dream was coming to Harvard, and what the academy did for me was to help me see it as a goal rather than just a dream.”

The program brings in 30 students each year, and officials are confident the ripple effects benefit the students’ families, schools, and communities. “We’re sending out leaders into the world,” said Rodburg.

Ariana Serret, who is going to Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, is one of them. She was awarded a Posse Foundation scholarship that will pay for college.

“My mom came from the Dominican Republic and couldn’t finish college,” Serret said. “She said to me, ‘Now you can graduate for me and for us.’”

As more low-income students entered Harvard, officials noted that many were the first in their families to go to college. The number of first-generation students has risen from 5 to 15 percent of enrollment in recent years.

Attending Harvard for free gave these students the same shot at success as their more-privileged peers. But without the connections or resources that those peers enjoy, the first-generation students sometimes found themselves struggling. Many didn’t know how to approach professors, use office hours, or apply for summer internships, which are part of the college experience often transmitted from parents to children.

In 2013, a group of students formed the Harvard First Generation Student Union to call attention to their needs and help them navigate the College. The administration responded quickly and created the Harvard First Generation program within the Admissions and Financial Aid Office, led by Dean William Fitzsimmons ’67, himself a first-generation student.

It was the right thing to do, said Claudine Gay, dean of social science in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the Wilbur A. Cowett Professor of Government, and professor of African and African-American studies.

“Harvard and other universities need to be prepared to respond to the needs of first-generation students who didn’t have the advantage of going to a private high school,” said Gay. “If we really want to have a diverse student body and if we really want to address inequality on campus, we need to be prepared to offer resources and support to make sure those students succeed.”

The office pairs first-gen students with Harvard alumni and provides resources so that students can take better advantage of the college experience. It also works to recruit more first-generation students to apply to Harvard and other colleges. That’s part of reducing inequality at Harvard, said Niki Alicia Johnson, the first-gen liaison in the Financial Aid Office.

“We try to reduce inequality by guiding them through the transition process and putting them on equal footing with peers who have parents who have gone to college,” she said.

Helping elementary school students

For years, experts have known the ironclad relationship between a child’s ZIP code and his or her chances of success. Despite efforts to close the achievement gap in school districts across the country, it persists.

The Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) recently launched By All Means, an effort to change conditions for the better in six places: Oakland, Calif.; Louisville, Ky.; Providence, R.I.; and Salem, Somerville, and Newton, Mass.

The Education Redesign Lab at HGSE will operate the program, which will connect superintendents, city officials, and community leaders with Harvard faculty to devise strategies to help children reach their potential, such as incorporating social and health services and high-quality, out-of-school learning experiences.

For Paul Reville, founding director of the lab and a former Massachusetts secretary of education, the initiative represents a renewed and necessary effort to achieve equity.

“Schools alone, as currently conceived, can’t do the job of educating all children for success,” he said in a statement. “We can do better.”

Providing communities with dental care

When Lisa Simon graduated from the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (HSDM), she knew she wanted to dedicate herself to working in underserved communities. As a dental student and as a resident, Simon took part in student volunteer programs within HSDM that offered dental care in homeless shelters and at a pediatric dental clinic in Cambridge. The work fostered her yearning to help those who lack resources.

“As a student, the outreach efforts to help vulnerable populations helped bring home why I was studying to be a dentist,” said Simon.

Now an instructor in the Department of Oral Health Policy and Epidemiology, Simon works in the Office of Global and Community Health at HSDM and supervises dental students who treat patients with special needs, as well as treats homeless and low-income youth. She also volunteers each week at the Nashua Street Jail.

In fiscal 2014-15, the pediatrics clinic covered nearly 300 patient visits and free dental care, while the homeless clinic helped 50 patients with fillings and treatment. In addition, the Crimson Care Collaborative, a faculty and student collaborative practice at Massachusetts General Hospital, provided oral care for 200 patients and more than 50 dental screenings. But the need is bigger, said Simon.

“We’re making a drop in the bucket,” she said, “but we’re banking on the fact that [by] giving students the opportunity to work in these settings and see the extent of need and the reward that comes from collaborating with these communities, we’d empower them to dedicate all or part of their career to address these disparities.”

Stamping out health inequities

Whether sending doctors to fight tuberculosis in Peru, Ebola in Sierra Leone, HIV in Rwanda, or offering free health screenings much closer to home, HMS works to balance health disparities.

Partners In Health, a Harvard affiliate that offers free health care to people as far away as Haiti, Lesotho, or Russia, tries to stamp out diseases caused by health inequities. But HMS is also preoccupied with what happens at home, particularly with recruiting minority faculty, students, and staff, and reaching and helping the underserved communities that surround the imposing, marble-faced buildings in the HMS quadrangle.

In charge of dealing with those pressing needs at home is Joan Reede, dean for diversity and community partnership at HMS. From her Gordon Hall office, Reede oversees programs that provide leadership, guidance, and support for minorities interested in careers in medicine, academic and scientific research, and health care. In her role as faculty director of the community outreach programs, Reede also makes sure the School offers programs for middle school and high school students to get them interested in college and science.

“My job is not only to recruit and increase the representation of minorities among faculty and students at the Medical School,” said Reede, a pediatrician. “Diversity is a component of our values. As our society becomes more diverse, the pool of students we choose from is also more diverse. If we want to stay true to our values, we have to make sure that we continue to get the best of society into our profession.”

Changing demographics make a diverse faculty a necessity, said Reede.

One of the programs she is proud of is Project Success, which brings students from Mission Hill, Cambridge, and Boston for summer research internships at the Medical School.

Sheila Nutt, director of educational outreach programs at HMS, said the programs help to project an image of Harvard as a good neighbor in the community, but also showcase the need to increase diversity among faculty and students.

“We’re very happy about the pipeline we’ve created,” said Nutt. “We have some students who have been with us since grade eight.”

The programs instill a feeling of belonging and empowerment, said Reede. She tells the story of a girl who was shocked when she saw a doctor wearing a basketball shirt underneath her white coat.

“The youngster asked the doctor, ‘Can you like basketball and science at the same time?’ They come here, and they start feeling they can be a part of this, that they could belong in here. These youths, they’re important in and of themselves; they’re the future.”

To inspire students, Reede often shares her own story. She was the first in her family to go to college.

“My great-great-grandmother was a slave,” she said. “And now, the great-great granddaughter of a slave is the dean of diversity at Harvard Medical School. I think that’s awesome.”

Gazette staff writer Alvin Powell contributed to this report, which was originally published in the Harvard Gazette on March 21, 2016.