Their pact started as a bit of a lark. Though the Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition was born at Harvard Law School in 1960, the school had never won the world championship. So, the 2022 HLS team members vowed to get matching Jessup tattoos if they took home the top prize.

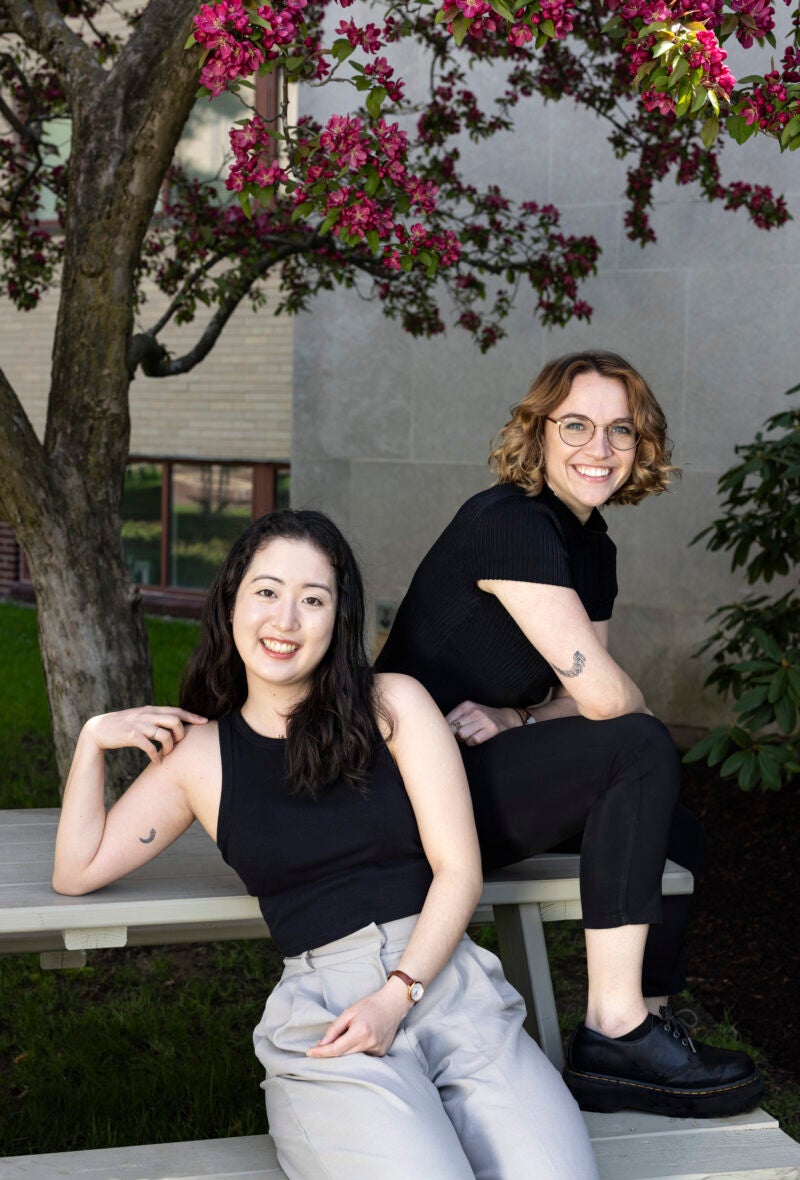

In April 2022, Harvard Law School prevailed over 600 teams from 85 countries and walked off with the Jessup Cup for the first time. True to their word, Marta Canneri ’22 — who was named best oralist in the final round — and Hannah Sweeney ’24 headed out the next day to a tattoo parlor on Massachusetts Ave. in Cambridge for a permanent tribute now inked onto their triceps. A few weeks later, two other team members, Katherine Shen ’22 and Nanami Hirata ’23, also got Jessup tattoos.

“It was an inside joke,” said Sweeney, “because a major principle of international law is Pacta sunt servanda” — literally, “agreements must be kept” and states are bound by their promises. “Thus our agreement to get tattoos must be kept.”

The tattoos are colorful evidence of just how central Jessup becomes to the lives of those who compete. The largest moot court competition in the world, Jessup simulates a fictional dispute between two countries argued before the International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. Each year, some 600 teams from around the world are presented with a timely problem of international import, and each team dedicates hundreds of hours in research, brief writing, and oral advocacy practice preparing for the competition in the spring.

The experience not only sharpens intellectual and practice skills, but fosters a close-knit community among teams, their coaches, and advisers. Over the past six decades, Harvard Law students, faculty, and alumni have been deeply involved in all facets of the event, from competing to coaching to serving as judges to writing the annual Jessup problem.

This year, Sweeney and Hirata competed again (the others on the championship team, including Stephanie Gullo ’22, graduated last year). In March, the 2023 team — which also included Ariq Hatibie ’24, Nick Caputo ’24, and Yen Ba Vu ’24 — took second place in the New York regionals and won best overall memorial (as the written submissions are called). They went on to participate in the Jessup White & Case International Rounds in April, in Washington, D.C., the first time the international rounds were held in person since before the pandemic. They were knocked out in the round of 32 but won best oral arguments and also best memorial. And at the end of May, they heard they’d also won the Richard R. Baxter Award, which places the top 20 written submissions of the world championship under fresh scrutiny.

“We were ecstatic,” said Hirata, noting that they regularly debriefed “Baxters” from previous years.

Sweeney shares her excitement. “Jessup is very clearly the best thing that has happened to me at HLS. It has been the most invaluable part of my legal education,” she said. And, like so many Jessup alumni, after she graduates, Sweeney plans to “continue to judge or coach future Jessup rounds indefinitely,” she added.

“Jessup is very clearly the best thing that has happened to me at HLS. It has been the most invaluable part of my legal education.”

Hannah Sweeney ’24

“One thing I’ve always found very impressive is that the students involved from four or five or six years ago are still extremely interested and invested in how the team does,” said Andrew B. Loewenstein, an expert in public international law at Foley Hoag who has advised the Harvard Law team since 2018. “They come back and serve as practice judges or are cheering from afar, so it’s a terrific way for alumni involved in this very seminal experience to continue to be engaged with their successors.”

“When you talk to a Jessup person, even if you never knew them before, they very quickly become a very good friend,” said Xuejiao “Katniss” Li LL.M. ’23 — a big fan of “The Hunger Games” — who added that Jessup is “one of the most important things in my life.” Li participated for five years in China, including while getting her master’s degree in law, during which time she was named national champion and won best oralist and best memorial. As an LL.M. student at Harvard this past year, she was a judge of the Chinese rounds — in which 61 schools participated via Zoom — and also a judge for the D.C. regionals of the U.S. competition, which did not include Harvard Law.

“Jessup will allow you to think creatively” no matter the particulars of the moot problem, said Li, who plans a career in international law. “Most of the time you can’t find [answers] in the textbooks. It’s your imagination, your attitude toward the world [that] will allow you to solve challenging problems facing the world.”

Origin story: ‘It was exciting, it was brand-new’

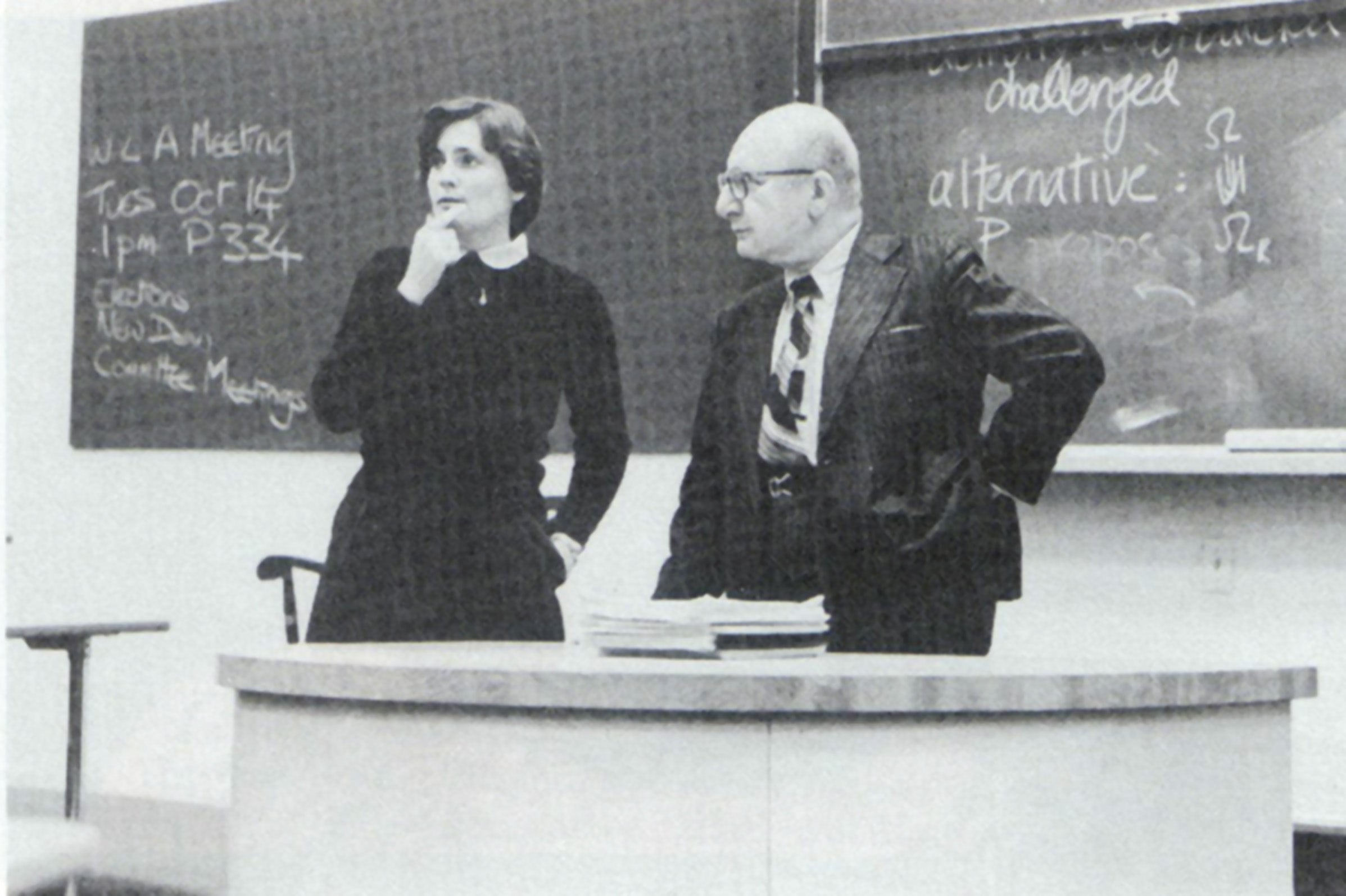

The Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, originally called the International Law Moot, started as a friendly competition among four Harvard Law School students — two Americans and two international students — to explore a timely question of international law through a simulated oral argument before the International Court of Justice. It was the brainchild of longtime Harvard Law Professor Richard R. Baxter ’48, who collaborated with Professor Stephen M. Schwebel, later an ICJ judge, to create the event.

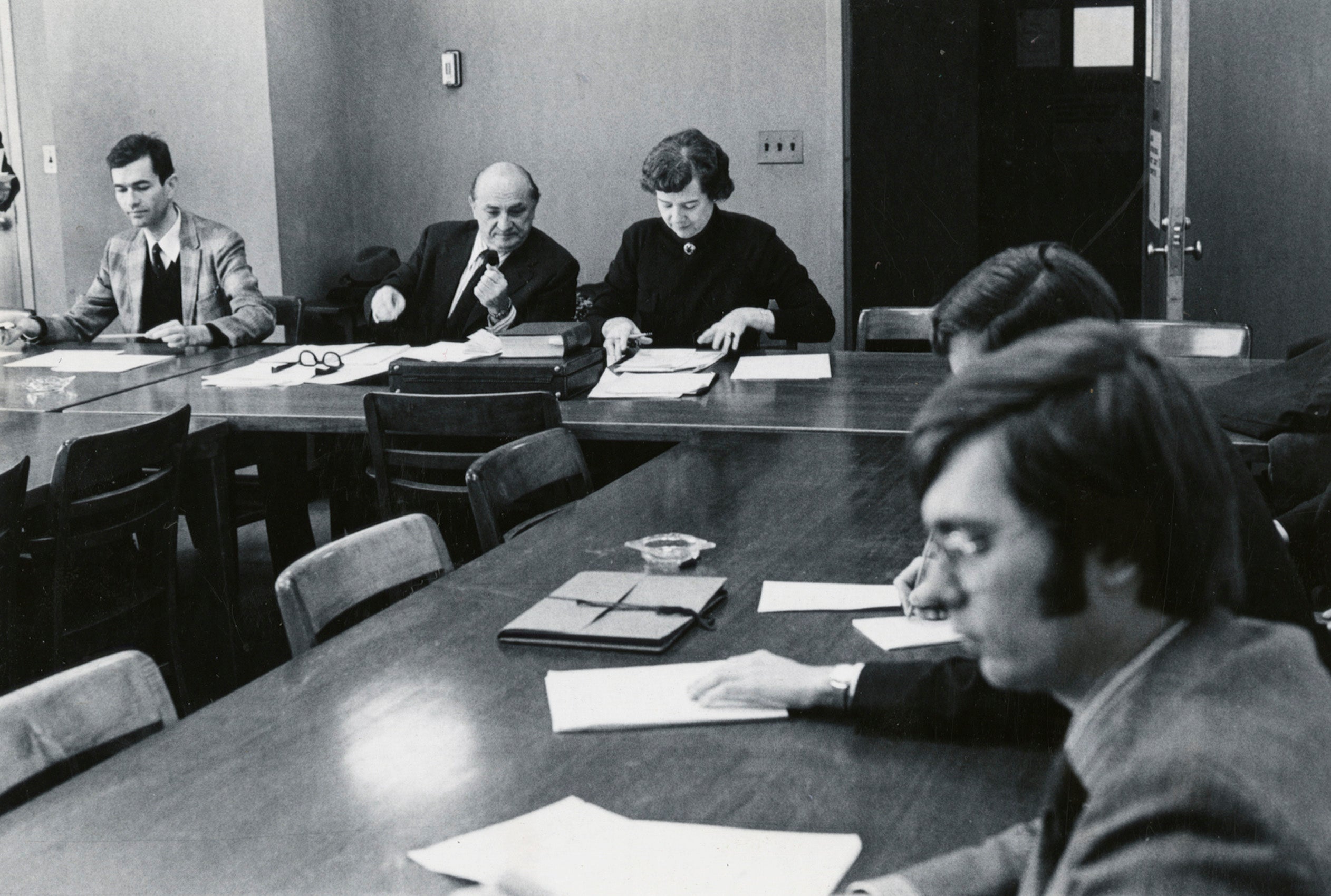

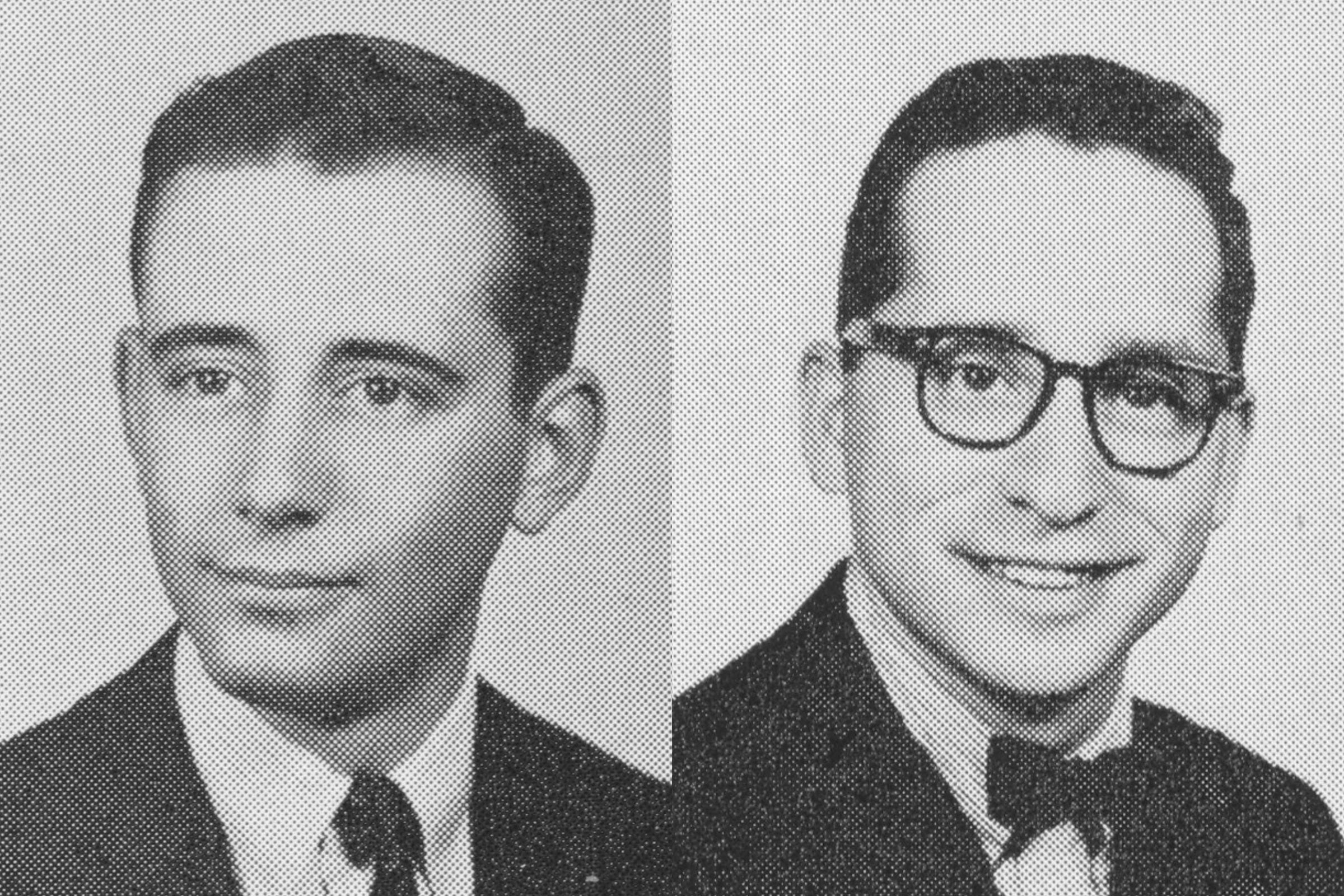

The first event took place at Harvard Law School on May 8, 1960, with Tom Farer ’61 and William Zabel ’61 representing the U.S. against two LL.M. students, Ivan L. Head LL.M. ’60, a Canadian student who would later become a foreign policy adviser to Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, and Bernard H. Clark LL.M. ’60 of New Zealand. Their problem, “Cuban Agrarian Reform Case,” was written by Schwebel, and final-round judges included Harvard Law Professor Roger Fisher ’48, a pioneer in the field of international law and co-founder of the Harvard Negotiation Project, and Milton Katz ’31, former administrator of the United States Marshall Plan in Europe, who taught international law at Harvard.

“It was exciting, it was brand-new, and the more interesting question to me is how we got picked,” recalled Zabel, laughing, “because we didn’t have any particular knowledge or expertise in international law, and also we were so young. I guess they did it because of our debate history.” As undergraduates at Princeton, Zabel and Farer served together on the debate team. That first Harvard Law competition, in which no winners were declared, was “mostly fun,” added Zabel, and though he participated only once, it spurred his interest in international law at a time when “there weren’t many ways to get involved.”

Zabel was an associate at the law firm Cleary Gottlieb before forming his own firm. He has made important contributions to international human rights and civil rights, including writing an amicus brief for the ACLU in Loving v. Virginia, in which the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967 declared anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional. Still active in law practice, he said he doesn’t remember much more about the birth of Jessup. “It’s just so long ago — I’m happy to be alive to talk to you about this,” Zabel said. “But you can certainly say Tom and I gave it our all.”

Farer, who served for years as dean of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, where he continues to teach human rights and U.S. foreign policy, also has fond memories. “Since I loved to debate and had been very successful [at it], and since I liked Bill, and because I was interested in things international, of course I was going to do it, and the topic interested me,” said Farer, who also served as president of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. “I was very interested in Cuba and Castro, and I think we defended the position that Castro’s confiscation of U.S. property was a violation of international law, but I would have been quite happy with either side of the issue. The topic was ripe and I thought it would just be fun, and it was fun.”

In the 1963 competition, champions were declared for the first time. In 1968, the competition was opened to non-American teams, and Baxter, the first holder of the Manley Hudson Chair of International Law at Harvard Law School and later a judge on the ICJ, renamed it the Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition in honor of the diplomat and international law expert who served for years on the ICJ.

Jessup has grown into an enormous worldwide event, with many Harvard Law alumni and faculty deeply involved over the years: David J. Barron ’94, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit and HLS’s Louis D. Brandeis Visiting Professor of Law, was among the authors of the 2009 Jessup problem, or Compromis, as it’s known. Amir Farhadi LL.M. ’18, who was a member of the Jessup Team at Sciences Po Law School in Paris that won the 2016 French National Championship, co-wrote the problem used in the 2020 competition. Farhadi works on ICJ cases with Loewenstein at Foley Hoag and continues to assist the HLS team with practice rounds.

“It’s nice to find a community … that embraces the world and is committed to changing it for the better, using the common language of international law.”

Ariq Hatibie ’24

Jessup has long presented an opportunity for J.D. and LL.M. students to collaborate. Shayan Khan LL.M. ’22, who had participated in Jessup’s international rounds during his LL.B. studies in Pakistan, coached the 2022 championship team along with team advisers María Laura Pessarini LL.M. ’22 and Loewenstein. And Peter L. Murray ’67, a visiting law professor at Harvard, taught a tailored workshop for the team, Oral Argument before International Tribunals.

Last year’s Compromis involved disinformation and freedom of expression, botnet takedowns, the secession of part of a nation’s territory, and foreign election interference. Team members cited the course Public International Law, taught by Professor Gabriella Blum LL.M. ’01 S.J.D. ’03, as laying a strong foundation for researching the issues that arose in the case. And in addition to Blum, said Sweeney, professors in other international law classes she’s taken have been very helpful, including Naz K. Modirzadeh ’02, founding director of the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflict, and Ioannis Kalpouzos, a visiting professor who specializes in public international law.

The competition, which is administered by the International Law Students Association, “has shaped my entire career goals,” said Sweeney. “Before I entered law school, I was not entirely sure what public international law litigation looked like in practice. I found the answer in Jessup.”

“I think the central value is that it forces students to engage deeply with a very complicated set of factual legal problems where there is no clear-cut answer, so it really compels students to develop their advocacy skills. … It’s a phenomenal way to prepare for actual legal practice.”

Andrew Loewenstein

This year, the Harvard Law School team was coached, along with Loewenstein, by Sagnik Das LL.M. ’19, who is currently an S.J.D. student. The Compromis involved the interpretation of a peace treaty, deadly attacks in allegedly occupied territory, unilateral economic sanctions, and the legal consequences of failing to dispose of hazardous waste properly. In the fall, team members spent roughly 10 to 15 hours a week working on research and writing, said Sweeney, and in January they worked almost full time on the memorials. In the spring, they practiced roughly 20 hours a week, and while at competitions, they mooted full time every day. “It is a lot of work and certainly only makes sense for public international law nerds who are truly passionate about international law,” said Sweeney.

“I think the central value is that it forces students to engage deeply with a very complicated set of factual legal problems where there is no clear-cut answer, so it really compels students to develop their advocacy skills because it’s not like they can just look up the answer somewhere,” said Loewenstein. “It’s a phenomenal way to prepare for actual legal practice,” whether in international law or not.

“I truly think they are some of the most incredible legal minds I’ll meet here — and probably anywhere — and are most importantly so compassionate and fun to be around,” said Hatibie, who was on the 2023 team. “It’s nice to find a group, indeed a community — shout-out to all the professors and LL.M.s who have taken the time to judge us — that embraces the world and is committed to changing it for the better, using the common language of international law.”

Loewenstein said the HLS teams he’s worked with have been “uniformly excellent.” Last year’s team, he added, was special in the way its members displayed “absolute dedication to really understanding the subject matter and putting in the time and effort,” as well as truly “innovative legal advocacy skills.” More broadly, he said, Jessup “really forces students to cooperate and engage with each other in a way that enhances everybody’s abilities.”

“It is a life-changing program,” said Sweeney, and — as her tattoo attests — “a lifelong commitment.”