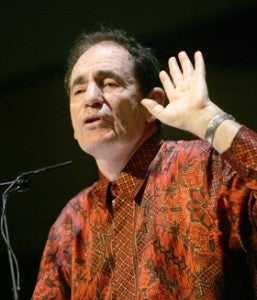

On September 12, Justice Albie Sachs, who served on South Africa’s inaugural Constitutional Court from 1994 through 2009, visited Harvard Law School for a screening and discussion of “Soft Vengeance: Albie Sachs and the New South Africa” with filmmaker Abby Ginzberg. An anti-apartheid activist, Justice Sachs spent 23 years in exile and survived an assassination attempt in which he was severely injured.

Sachs returned to South Africa following the release of Nelson Mandela and played a prominent role in the drafting of South Africa’s post-apartheid Constitution. For these and other contributions, Sachs received the inaugural Tang Prize for Rule of Law, selected by an eminent international panel of jurists and awarded in Taipei, Taiwan soon after his visit to Harvard.

Following the screening, Justice Sachs thanked HLS, noting that: “It’s the first time I’m seeing the film in a law school; it makes a big difference. I’ve seen the film many, many times, and each time the audience is a dancing partner–so it’s a different experience, and it’s very emotional to me. I’ve been to Harvard many times in many different ways and it’s a place I feel exceptionally at home; it’s a very significant place. But to see this film and to feel the response of the audience it’s actually quite overwhelming for me so thank you for inviting me.”

Sachs and Ginzberg then took questions from the full lecture hall, for more than an hour. Many explored Justice Sachs’ extraordinary life history, both in itself and for what it said about South Africa’s transition from apartheid. He was asked about his meeting (described in the film) with one of the apartheid-era police officials involved in the assassination attempt. In response, Sachs stressed his profound commitment to what he termed “soft vengeance” – namely, the idea that rather than perpetuate a cycle of violence, one should enable those who perpetrated violence to understand and publicly acknowledge the great harm they had caused, thereby advancing reconstruction for the nation, for the victims, and even for the perpetrators.

Several other questions touched on his native land more generally. Reflecting on South Africa’s democracy process, Sachs said, “We used to hear the reactionaries saying ‘come on, democracy will never work, black and white will never function together in one country, let’s get real’ and we refused to get real, we insisted on being ideal, and we were right.”

Sachs also gave advice for those attempting to bring about change: “I don’t think you should follow in our footsteps because our footsteps were guided by the ruthlessness of oppression…sometimes you restrict your imagination because you’re just focused on freedom, freedom, freedom. And you’ve got to have much broader minds than we had, and you don’t have […] to risk death and torture and being sent into exile, and you don’t need the methodology of struggle appropriate to that.”

These sentiments were echoed by Ginzberg, who spoke about the years of research that went into the film, which was the latest of a series of documentaries the law trained film maker has made about social justice. As noted by Vice Dean Bill Alford ’77, who was their host at the Law School and who extolled Sachs’ vision, courage and creativity, “Soft Vengeance” has already won awards at film festivals in Canada and South Africa.

Questions also concerned the drafting of South Africa’s constitution. One student asked “What model did you use when drafting the constitution, what was your inspiration when writing the bill of rights?” Sachs replied by indicating that “we used the constitution of the United States of America.” Sachs and others involved in the process also examined and drew from the constitutions of Germany, India, the United Kingdom, Namibia, and Canada, among other nations. “Your constitution came out of a revolution, people fighting for freedom. And it encapsulated a mechanism for how [to] manage sovereignty without a sovereign. The U.S. provided us with that model of separation of powers and also the notion of fundamental rights, and the notion of the testing power–instruments to ensure that these fundamental rights could withstand passions, popular pressures, injustices heaped upon scapegoat sections of the community.”

At the same time, Sachs, in response to a question regarding the meaning of this summer’s tragic events in Ferguson, Missouri, indicated that while the U.S. had made considerable progress since his first visit some 40 years ago, much more remains to be done and, in some ways, the political atmosphere in general had become more polarized. Sachs concluded the session, following a question about what advice he would give to current defenders of human rights, by offering his theory of the conservation of progressive energy: “By its very nature energy can’t dissipate—often you don’t see the outcomes, but it’s lurking there and it can come out, so I say not to be impatient to see outcomes, and not to give up on making the progressive effort.”