Since 2000, Jacksonville’s Black population has risen, even as the share of white residents has plummeted by 11 percent. But the demographic changes that might have led to greater representation for African Americans in this city in northeast Florida have failed to do so. That’s because the new city electoral map, drawn after the 2020 census, unfairly and illegally packed Black residents into four districts to limit their political power, local advocates allege.

Rosemary McCoy is among the many plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by Harvard Law School’s Election Law Clinic in partnership with the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the ACLU of Florida, representing the Jacksonville Branch of the NAACP, three other local organizations, and nine other Jacksonville residents. In 2021, she described the right to vote as a matter of “life or death.”

In a time when wins for voting rights advocates feel rare, the lawsuit has already had several important successes, says Daniel Hessel, attorney and clinical instructor at Harvard. Last October, a court agreed with the plaintiffs, jettisoning the gerrymandered map and replacing it with one that addresses the most egregious problems of the original. And now, thanks to an early-January victory in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, that interim map will be in place during the upcoming election for city council in March 2023.

“I think the wins that we’ve had in this case are increasingly rare in the civil rights sphere generally, but definitely in voting rights given what has happened in this area recently,” says Michaela LeDoux ’24, a student in the clinic.

But the Jacksonville activists and the Election Law Clinic are not done. Their ultimate goal is the adoption of a map that best reflects the growing population of people of color in Jacksonville — and ensures that electoral power in the city is fairly distributed.

On the map

Jacksonville has long had an issue with racially gerrymandered municipal districts, says Hessel, adding that the problem has only become more glaring as the population of Black residents has increased, but their share of political power has not.

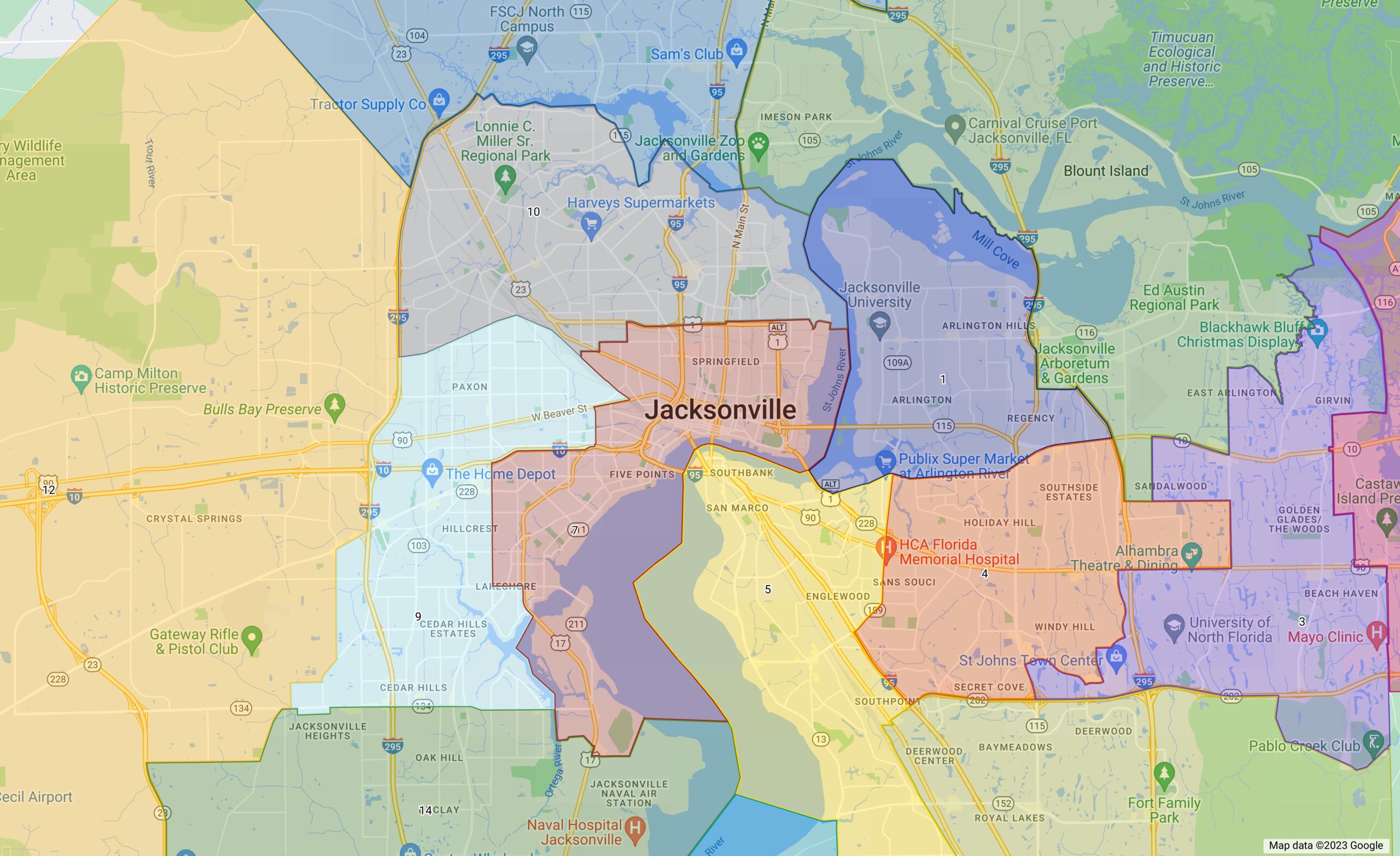

“For quite a few decades now, Jacksonville city council districts have packed Black voters in the northwest side of the city into four city council districts out of 14 total districts,” says Hessel, “And when I say packed, I mean they have made every effort to put as many Black voters in those districts as possible — to the tune of well over 50%, and in some cases, 70%.”

This leaves the surrounding districts artificially white, diluting the power of Black voters in those districts to elect city council and school board members of choice, says Ruth Greenwood, director of Harvard’s Election Law Clinic. “This is a case where you have a growing community of people of color, in particular Black voters, who are consistently getting left out from representation.”

And the harm is not theoretical, she says. Municipal government, and city council, control many things that impact peoples’ daily lives, like resource distribution, public hiring, and the police. And with fewer opportunities to be elected at the city level, candidates of choice who may have eventually gone on to roles in the state and federal government may never have the chance – blocking an important pipeline for talented leaders of color.

Jacksonville strikes back

In 2021, even before the clinic got involved, voting rights proponents in Jacksonville were raising concerns about the map, says Greenwood. At first, the clinic worked to amplify those voices, hoping that the city council would reject the map on its own.

“We worked with people on the ground who were complaining about the map to try to get a solution,” says Greenwood. “Before the maps were passed, there were a whole lot of people that stood up at the meetings and said, ‘We think that this is a problem, and you should do something differently.’ And this council didn’t listen.”

The next step, says Greenwood, was to file a lawsuit challenging the racial gerrymander. “This is one of the few causes of action that is still allowed in the voting rights space,” she says.

Kunal Dixit ’24 is another clinical student working on the case. He says that it is important to show that the Jacksonville City Council and the redistricting committee, who redesigned the electoral map, used race when they drew the packed districts.

And while drawing districts by race is not always unconstitutional, adds Hessel, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that the use of race must be “tailored carefully and narrowly to a compelling interest like compliance with the Voting Rights Act,” he says. “Here, Jacksonville made no such efforts. It has all but conceded that the Voting Rights Act does not require percentages of Black voters as high as these four packed districts have.”

In its defense, the Jacksonville City Council has claimed it was merely carrying forward the cores of previous districts, and that it was trying to protect incumbents — not discriminate by race. “Both of those reasons are usually considered legitimate for a City Council to use, except when those considerations are just being used as proxies for race, where the real motivation was race,” explains Dixit.

It’s a high bar for plaintiffs in cases like these to show that the true motivation was race, he adds. Which is why, when a federal district court agreed with the plaintiffs last fall and issued a preliminary injunction, the clinic and its allies were thrilled.

The fight continues

The injunction, which is a temporary measure while the case works its way through the courts, meant that the original map could not be used, so Jacksonville’s City Council was tasked with coming up with a second map to fix the racial gerrymander in time for the March election. But this map, too, was flawed, says Dixit.

“So, we challenged that new map and also succeeded in that challenge,” he says. “And the district court judge adopted one of the three maps that we had presented to the court as alternative interim remedies.”

Although it had already lost twice, Jacksonville’s City Council appealed the lower court’s decision, looking to reinstate its own interim map. And yet again, in an important win for voting rights advocates and the clinic, the 11th Circuit sided with the plaintiffs, refusing to issue a stay of the district court’s decision. The plaintiffs’ map — the one that cured the worst problems with the original districts — would be in place for the March election.

“Jacksonville is a diverse city, but Black voters don’t necessarily feel like their voices are heard or that they have much of an opportunity to meaningfully influence public policy,” says Hessel. “I think that our initial wins are a really important step forward in changing that. And our goal moving forward is to make those preliminary wins permanent and cement fair representation in the city.”

A reverberating impact

Dixit and LeDoux say that it has been a thrill to work as students on a lawsuit that could have a positive impact on voting rights in Jacksonville and even more broadly.

“We’ve gotten to be part of every aspect of this case, from writing briefs and doing the legal research, to even interacting with co-counsel and community members,” says LeDoux. “Some of our classmates got to go down to Jacksonville in the fall and meet some of the plaintiffs who are part of the case, including individuals from the community and major civil rights organizations.”

For Dixit, a key lesson has been the importance of building local relationships in voting rights litigation. “We have a phenomenal group of plaintiffs who are not just residents of these districts but who have also been leaders in the Jacksonville community for decades and decades,” he says. “To tailor everything that we did — the maps that we drew, the arguments that we made — to the needs on the ground that they had experience with and were able to share with us … that was really cool.”

Like Dixit, LeDoux says she enjoyed putting pedagogy into practice. “It has really been so special, that just as second-year students, we’re able to be part of something like this — it’s kind of unreal,” she says. “It’s such an amazing opportunity to come to law school and see how the things I’m learning in class apply to a case with important civil rights implications.”

Now that the preliminary stages of the case are over — with an injunction on the original map in place — Hessel says the suit will move into ordinary litigation, including discovery and fact-finding, and potentially a trial that will determine whether the original map was illegal after all. “We’re hopeful and quite confident that the judge will issue a permanent decision enjoining the first map,” he says.

If the suit is ultimately successful, it could have an impact on other voting rights cases, potentially even one currently before the Supreme Court, said Greenwood. “Take Merrill v. Milligan. That case has only gone up to the Supreme Court on the Section Two [of the Voting Rights Act] claim, but if that gets rejected, then it will go back to the Alabama district court on the racial gerrymandering claim,” she says. “The law that we have now set at the 11th Circuit, on some of these issues, will be binding authority on that court.”

The plaintiffs in the case — the Jacksonville activists who have been emphatically challenging the maps since before the lawsuit — are also hopeful. As Rosemary McCoy told the ACLU of Florida last year, “Maps that give Black communities an equal voice will be vital for securing equal investment, equal funding and equal attention for our communities from our city government.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.