Once or twice a month, David Lammy LL.M. ’97, Britain’s deputy prime minister, can be found in Tottenham in northern London, making the rounds and meeting with constituents. On a recent Friday, he stopped in the morning at a mental health center and later met with the head of policing before sitting at the local library with residents eager to air their concerns. That afternoon, he was bound for a nearby “elderly lunch club.”

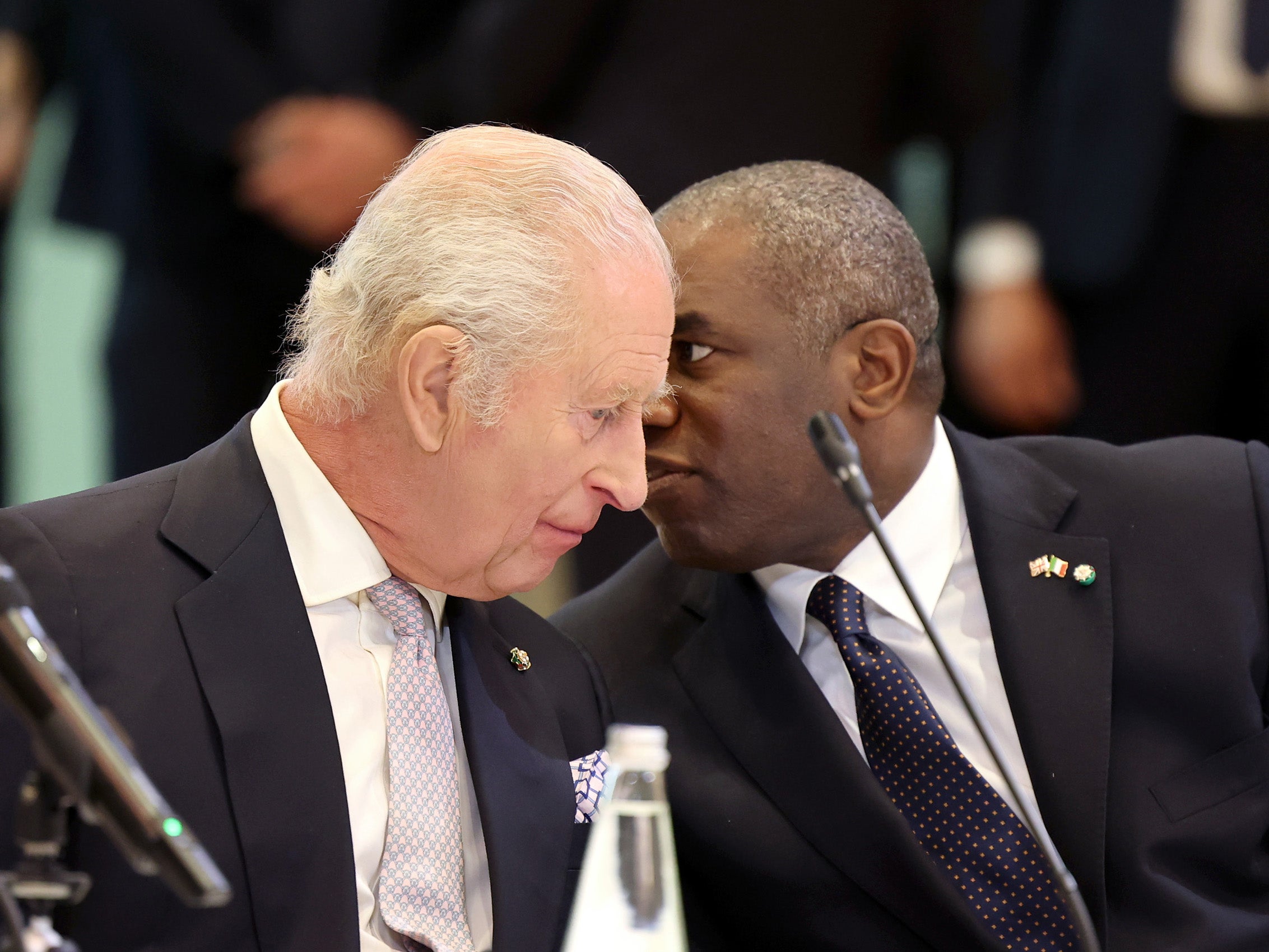

Lammy grew up in the area and launched his political career there, representing Tottenham as the Labour member of Parliament for 25 years, during which he was appointed the country’s foreign secretary in 2024. In September, Lammy was named deputy prime minister of the United Kingdom and lord chancellor and secretary of state for justice. The appointments came after he’d spent more than a year traveling the globe representing the U.K. on behalf of the current Labour government led by Prime Minister Keir Starmer.

Until September, Lammy had been busy brokering treaties on the world stage, addressing the United Nations, and visiting the White House. But he has also remained visible closer to home, standing up for the district he continues to represent.

As he has steadily ascended to the highest ranks of British politics and society, he says he has never lost faith in the power of his vibrant, hard-working community to thrive. “The one thing I would never change is where I grew up,” Lammy wrote in a 2011 memoir, “Out of the Ashes: Britain after the Riots.”

“It’s a wonderful thing that keeps your feet to the fire,” says Lammy, of his ongoing community work.

“It’s a wonderful, wonderful thing that keeps your feet to the fire about why we’re in politics,” says Lammy, in a recent interview, of his ongoing community work. “Obviously I’m a specialist in terms of foreign affairs, but it’s really important for me to remain connected to my constituents, to things that they care about, what they say to me, and to represent their interests around the cabinet and in political life.”

An early experience with rough times and resilience

Lammy considers his early life as largely happy despite the trouble, turmoil, and poverty that gripped much of North London in the 1970s and ’80s, including his home of Tottenham, a place he describes as a melting pot filled with immigrants from the West Indies, Ireland, Cyprus, and elsewhere. “We were all working class, didn’t have much money, and, I think, to some extent, felt slightly on the fringe of mainstream debate, discussion in the United Kingdom.”

Lammy’s parents, both immigrants from Guyana, worked hard to keep the family afloat, but there were tensions at home, he says, and his father eventually left the family when Lammy was 12. His mother took multiple jobs to support her five children. He calls her “a great friend and a great mentor,” who believed passionately in education and pushed him to succeed.

That success was helped early on by the opportunity for Lammy to attend a “very good school” in Peterborough, where he studied hard and sang in a cathedral choir. He persevered despite being routinely bullied and harassed as the school’s only Black pupil. “There was a bit of racism,” he recalls. “But it was a very pastoral environment, and it worked for me. It took me out of the inner city, gave me opportunities that I otherwise might not have had, and gave me some respite maybe from some of the hard knocks of inner-city life.”

It also gave him the kind of perspective on justice and fairness that often only comes from years of lived experience. “[You suddenly see] schools in this area are concrete, they’re rough, they’re not well-resourced, and in this [other] part of town, they’re well-resourced. Why are there no trees, green spaces here, but somewhere else, there are?”

In his memoir, Lammy describes watching the 1985 Tottenham riots unfold from the safety of his boarding school an hour away — riots that took place following the death of a Tottenham resident during a police raid. He was 13 and terrified that his family might be caught up in the violence raging near his childhood home.

“I watched in horror as the television showed my neighbourhood going up in flames,” writes Lammy, whose book outlines the deep social, economic, and political forces that fueled that conflict — as well as another outbreak of rioting in 2011 — and identifies steps to help communities move forward.

As a young teen, Lammy was also becoming increasingly aware of social unrest not only in Tottenham but around the world.

“This is a period where Nelson Mandela was still in prison [and] we were watching on our television screens huge injustice in relation to race and apartheid. It was an era of an Afrocentric Black America beginning to speak out against the injustices that were still being wrought on Black communities. … I started to think about social justice and injustice, and to connect the dots internationally,” he says. “That started to lift me up and empower me, particularly in the context of what I saw around me — the rioting and those sorts of issues —and I became very political. That took me towards law.”

Lammy would study law in college in London and planned to join one of the British Inns of Court, four professional London associations devoted to helping train and support barristers, but was dismayed by what he saw as the unfair treatment of Black students there. The students’ experience became a warning to Lammy, who remembers thinking, “If this is my fate, I better have a plan B.”

Enter Harvard.

Setting his sights on the United States

Long before he set foot on the Harvard Law campus, Lammy had become intrigued by America, after frequently making the summer journey from North London to New York to visit family in Brooklyn and Queens. He saw this trajectory reflected in the works of Black intellectuals, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Caryl Phillips, who captured in their writing the lure of something greater, Lammy says, and “the odyssey that minority Black communities make from places like London or Paris to America and then vice versa — African Americans, coming and spending time in London or Paris — and that was beginning to speak to me.”

Also influential for Lammy was a summer exchange program in New York City working with lawyers affiliated with the City University of New York. “It was about gifting us aspiration and showing us what was possible,” he says. “There was a sense that the United States had an emerging Black middle class, that we should be exposed to something that lifted us beyond our horizons.”

He applied to Harvard Law School, he says, “not really thinking about getting in,” and today considers his time on campus a privilege. “I was inspired by so many people there. I just immersed myself in the LL.M. Program and had a wonderful time.”

Heading west and then back home

Like many young students in his day, Lammy was drawn to the West Coast and the allure of becoming a California lawyer, thanks in large part to the spell of the splashy late ’80s drama “L.A. Law.” Instead of Los Angeles, he landed in San Francisco at the firm Howard Rice in 1997. But soon he found himself homesick and increasingly eager to be part of a new era of political reform he saw taking hold in the United Kingdom as well as in the United States.

“Politics was coming alive,” says Lammy. “Tony Blair had arrived on the U.K. scene … and Bill Clinton [was president] in the United States; progressives were coming to power, and I really wanted to come back home, and I decided at that point that I wanted to be a politician.”

The decision was fueled in large part by his time at Harvard, he says, where he developed the kind of self-assurance required to run for public office.

“I left Harvard Law School with tremendous confidence that propelled me to become a politician here at the age of 27. That would never have happened had I not gone to the United States at that time in my life. It was only America, only [a school like] Harvard, that could have lifted me up to that sort of confidence to come and stand for office here in the U.K.”

Lammy says he also often relies on the lessons he learned at Harvard in his political work.

“With the challenges that we have in the world, I draw a lot on Harvard as an institution,” he says, whether it’s been scholarship or people he has reached out to over the years. “Beyond the law school, the Kennedy School is hugely important as well,” he adds. “[Harvard’s] been a constant in my 25 years in public life.”

Looking at his political life

When discussing his career, Lammy breaks it down into “three big chapters,” beginning with his election to Parliament in 2000. Although he was dubbed the “baby of the House,” his youth didn’t stop him from getting things done. As a health minister in the Blair government, he established a framework for diagnosing and treating people most at risk of developing diabetes, and enacted reforms that reduced emergency room wait times dramatically.

Later, as minister of state for culture, he helped the U.K. commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade in Britain in March 2007. As an education minister, Lammy advocated for fair access for children despite class, race, or geography to the U.K’s top universities. “That was inspired by my experience of being at Harvard because Harvard was a diverse place, and I was very concerned that Cambridge and Oxford were far, far less diverse,” says Lammy, “and that’s gotten considerably better because of the work that I pioneered.”

In his second chapter, and with the Labour Party voted out of power, Lammy spent much of his time “finding my voice on the back benches” fighting for the rights of those underrepresented in the British system of government. As part of that effort, he argued for an inquiry into the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, on behalf of the 72 people who died in the blaze in the public housing complex, and he led an independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian, and minority ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system.

He also pushed back against Brexit, the eventual withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. “I took a strong position in Parliament at that stage,” says Lammy, “standing up to people like Nigel Farage [co-founder of the Brexit Party].”

He considers his third and current chapter that of an elder statesman. He served as shadow secretary of state for justice and shadow lord chancellor in Starmer’s shadow cabinet — the team from the opposition that mirrors those roles held by the ruling party — and was promoted to shadow foreign secretary in 2021, with Labour leader Starmer urging him to use his network, Lammy says, to “help forge relations with the United States.” When Starmer became prime minister in July 2024, he appointed Lammy foreign secretary. In September, Starmer named Lammy to his new posts as part of a cabinet reshuffle.

In retrospect, Lammy says that he is “staggered at how quickly [the time] has gone,” but he remains grounded by his upbringing and energized by his work. He remembers being warned by some people early on that “politics would make me quite cynical, but I think I’m still the same guy. I still have hope and optimism.”

A big part of his work is about finding common ground and forging connections. He considers himself a bridge builder and counts among his friends both former President Barack Obama ’91, whom he met in 2005 at a Harvard Law event, and current Vice President JD Vance, and he recently told The Guardian newspaper that he has a “really good relationship” with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

What Lammy brings to this particular work, he says, is relational. “It’s that business to get on with people — whatever their background, whatever their race, whatever their culture.” He credits Harvard with offering up a “wonderfully international environment” where he could learn from and engage with a cohort of students from around the globe. Harvard, he says, also taught him a key diplomatic skill: how to listen. He recalls being in a Harvard Law School class or one of the Harvard Kennedy School classes he sat in on, “just listening and just being inspired by these huge minds.”

Those lessons continue to resonate wherever his job takes him.

He recently traveled to Syria, the first foreign secretary of the U.K. to visit in 14 years. “I was there listening to agricultural women hoping for a better life now that [former dictator Bashar al-Assad] has fallen,” he says, “listening to the new leader of Syria and pressing him on whether he was turning away from the terrorism that he was associated with in the past.”

Lammy also recalls sitting in the occupied territories listening to Jewish families who had loved ones held hostage in Gaza, and to women who’d been abused in Sudan and were fleeing for their lives as their villages were ransacked. “That’s the key,” he says, “and I learned those skills in part at Harvard — that ability to listen beyond cultures and boundaries.”

When he is not working, Lammy loves taking in a film or a play. “If there’s an Arthur Miller going on anywhere in the U.K., you can trust me to go and find it and see it.” His passion for movies was inspired in part, he says, by the late Harvard Law School Professor Alan Stone, an authority on law and psychiatry who encouraged students to grapple with some of life’s most pressing questions. Lammy recalls how Stone “used film to discuss the kind of moral adventure” we’re on, adding that he was “a great, great man.”

Lammy also makes time to honor his Guyanese roots. He and his wife, artist Nicola Green, created Sophia Point, a research and education center in Guyana that works on rainforest conservation. “It’s a huge privilege,” says Lammy. “I have a love of that region of the world. It’s a way of giving back.”

A lifelong Tottenham Hotspur soccer fan, Lammy can be found on weekends at the Spurs’ stadium supporting the club, when his schedule permits. He recently took India’s foreign minister to a game and makes time each season for the North London Derby, the annual grudge match between powerhouse rivals and neighbors Tottenham and Arsenal.

“I always go with the prime minister … he’s a big Arsenal supporter,” Lammy says of Starmer. “And there’s always much controversy, because, sadly, Arsenal often beats the Spurs. But occasionally we win, and it’s something that usually lights up social media.”

Reflecting on his early days in politics, Lammy recalls how many of his constituents worried he was not up to the task of being MP.

“They weren’t sure when I was a younger man that I really got it, that I could really be there for them,” says Lammy. “They expect a kind of toughness; their lives are often tough.”

Twenty-five years later, he has proved his doubters wrong. Now when he walks through town, the reception is decidedly different.

“I’ve been particularly inspired in the last few years at the love,” says Lammy. “People toot their horns. They approach me. They want to shake my hand,” he adds. “They feel so proud to see me on an international stage, representing the country. So, it’s very humbling to represent my home. I know the streets. I have lived in this community all of my life, and I am inspired by it every single day.”