They are big and small, ornate and more than a little worn and weary looking. They are hundreds of years old, and they are all part of the Harvard Law School Library’s rich collection of Magna Carta manuscripts, including one that was recently determined to be an original from 1300. That historic find was made possible thanks to the library’s vast and ongoing digitization efforts that are rendering more and more of its collection, including its medieval manuscripts, visible online.

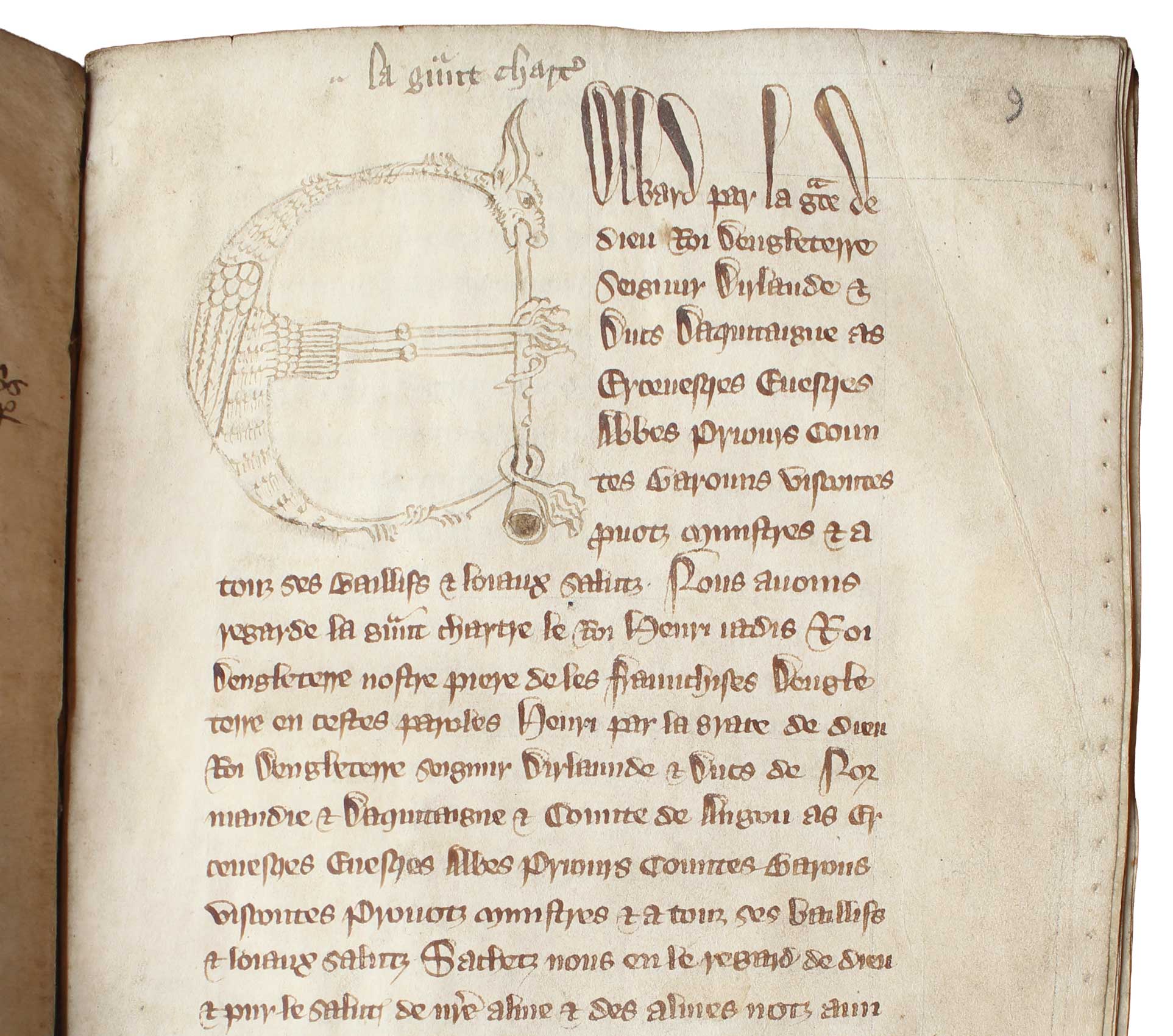

After some virtual sleuthing by two scholars in England, and with help from library staff who produced more detailed images of the delicate document using ultraviolet light and spectral imaging, HLS MS 172 was introduced to the world this spring as a genuine example of the historic document, making it one of only seven originals from King Edward I’s 1300 issue of Magna Carta known to survive.

This summer, the Harvard Law School Library mounted a small exhibit from its Magna Carta collection featuring a range of examples of the historic text that effectively decreed the king was not above the law and that has inspired democracies around the world. The law school also hosted a daylong Magna Carta celebration that featured panel discussions with law school scholars and librarians as well as with British researchers David Carpenter, professor of medieval history at King’s College London, and Nicholas Vincent, professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia, who together first suggested that the Harvard Magna Carta was a 1300 original.

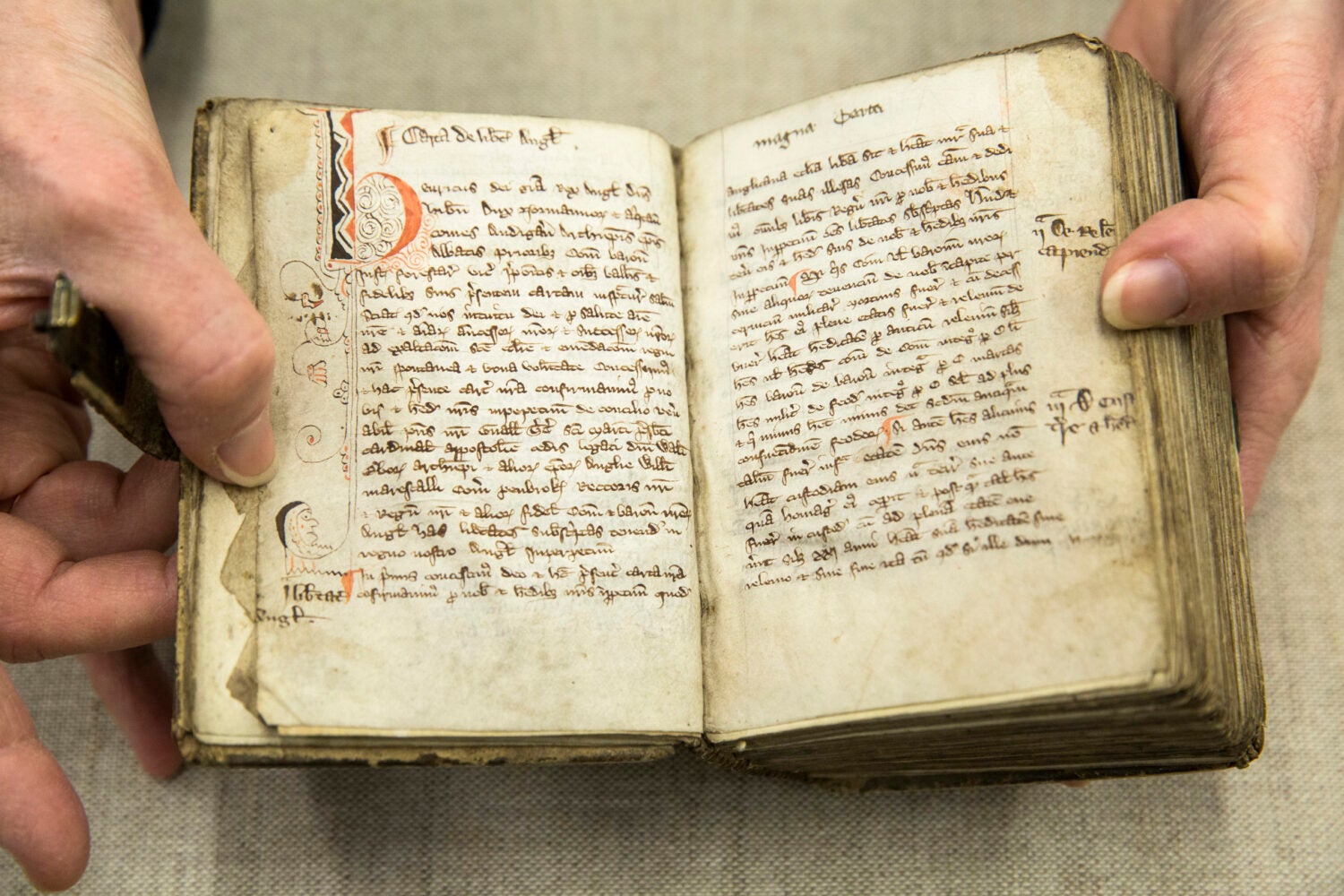

For many at Harvard, the law school library’s Magna Carta specimens are important teaching tools, representing a direct link both to the past and to the laws many governments follow today. Elizabeth Papp Kamali ’07, Austin Wakeman Scott Professor of Law and an expert in English legal history and medieval English common law, regularly taps into the library’s rich archives as part of her course offerings. She notes that most of the library’s Magna Carta examples are found alongside other important statutes in codex, or bound volume, form. Some of these books are ornate and pristine, suggesting they were produced as a prestige item for someone of considerable means. Then there are others that show their wear.

“For law students, seeing the well-used books of practitioners almost sends a chill down one’s spine, offering tangible, material evidence of the life of a practicing attorney from the 14th or 15th century,” Kamali says. In some sense, it’s the equivalent of what looking something up in Westlaw might have been for someone who was representing clients all those years ago, she adds. “For students, that’s a very powerful moment.”

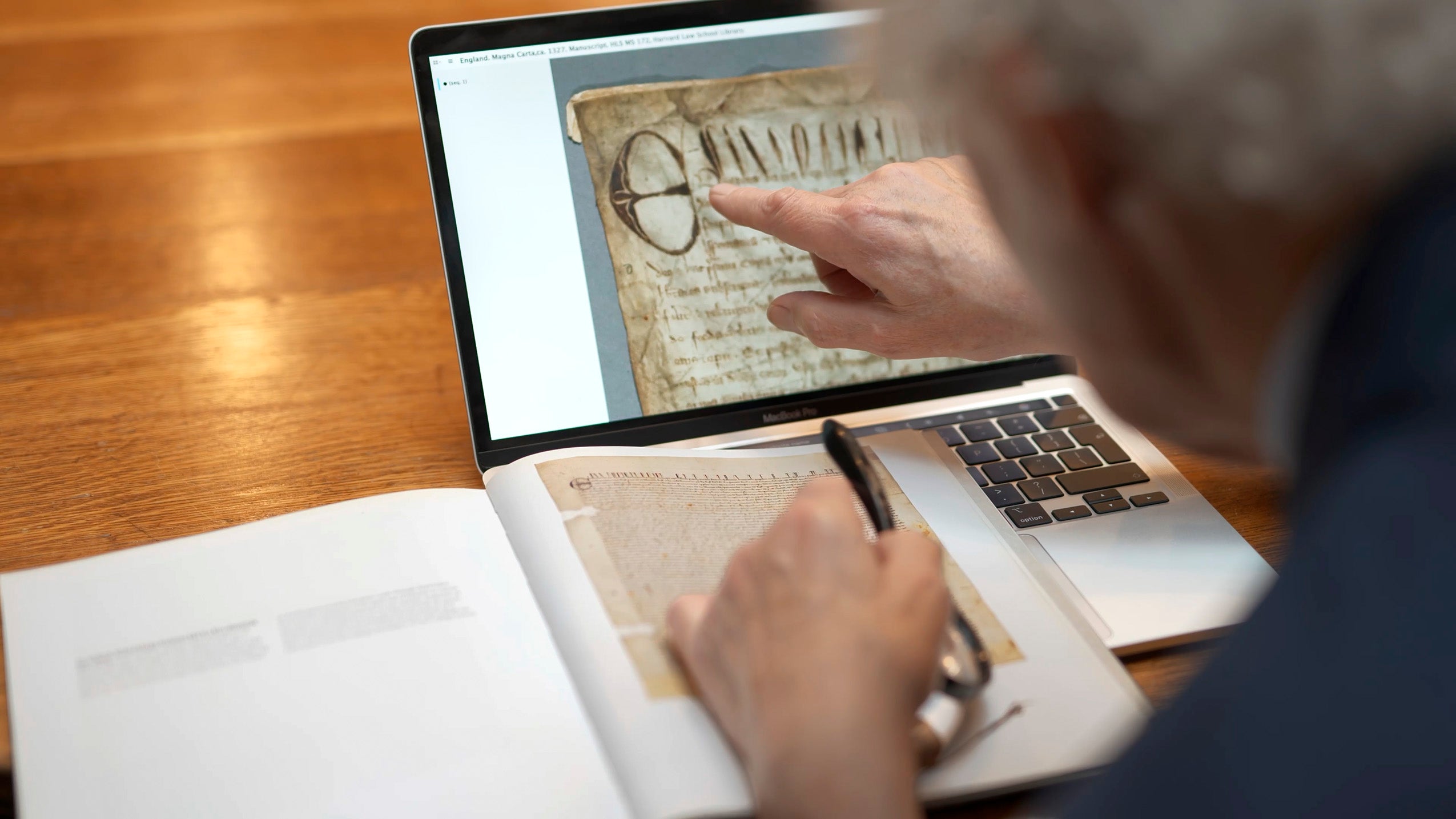

And although professors will no longer be able to take out the prized original document for teaching, students can still peruse the manuscript online, thanks to the library’s meticulous digitization efforts. It’s a change Kamali is more than willing to make.

“It won’t be handled in the way that it was handled previously, but that’s a trade-off that’s entirely acceptable under these happier circumstances,” says Kamali, who sees celebrating the new find as just another chance to revel in its history, lore, and legacy.

“When I joined the faculty here in July 2015, it was less than a month after the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta at Runnymede. I remember thinking I had missed the boat, that if only I had become a law professor a few months earlier, I would have been riding the wave of Magna Carta,” says Kamali. “In a way, this was a wonderful continuation of that celebration … to have another reason to think about the significance of Magna Carta as it was sealed in 1215, and as it was reissued after that, and as it has taken on new meaning generation after generation.”