People

David Harris

-

1 in 5 Prisoners in the U.S. Has Had COVID-19

December 18, 2020

One in every five state and federal prisoners in the United States has tested positive for the coronavirus, a rate more than four times as high as the general population. In some states, more than half of prisoners have been infected, according to data collected by The Marshall Project and The Associated Press. As the pandemic enters its tenth month—and as the first Americans begin to receive a long-awaited COVID-19 vaccine—at least 275,000 prisoners have been infected, more than 1,700 have died and the spread of the virus behind bars shows no sign of slowing. New cases in prisons this week reached their highest level since testing began in the spring, far outstripping previous peaks in April and August...Racial disparities in the nation’s criminal justice system compound the disproportionate toll the pandemic has taken on communities of color. Black Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of whites. They are also disproportionately likely to be infected and hospitalized with COVID-19 and are more likely than other races to have a family member or close friend who has died of the virus. The pandemic “increases risk for those who are already at risk,” said David J. Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School.

-

How Has Boston Gotten Away with Being Segregated for So Long?

December 9, 2020

When Sheena Collier moved here from Atlanta 16 years ago to pursue a master’s at Harvard Graduate School of Education, she was looking forward to getting her degree from one of the most prestigious universities in the country. What Collier was not looking forward to, however, was living in the Boston area. Collier, who had just graduated from the historically Black Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, had the very distinct impression that there weren’t a lot of people of color here. For her first two years in the area—during which she lived in Cambridge and Allston, interned for a while in Charlestown, and went out at night in downtown Boston—Collier didn’t see anything that changed her mind. Then she moved to Roxbury and began managing after-school programs there. “That was when my whole perception of the city shifted,” she says. “You start to learn that this is who lives in this neighborhood and this is who lives in that one. Boston is diverse—it’s just really segregated.” ... There is no shortage of plans and policy proposals that could help Boston and its suburbs become less segregated. But to turn those bright ideas into lasting change, we’ll need something more: a commitment to take on this debt to our Black community and invest in reversing the harm of decades of housing discrimination. When we talk about integration, it is important not to become enamored with shortcuts, nor to lose sight of the fact that “integration is not a pathway to social justice; it is a result of social justice,” says David Harris, the managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School.

-

In a close election, some Black Americans see a clear winner: Racism

November 5, 2020

Chad Williams, chair of the department of African and African American Studies at Brandeis University, admits he was optimistic heading into Tuesday night. He had hoped “America would get it right this time” and that Joe Biden would win resoundingly. But as he watched President Trump gain an edge in key swing states like Florida and North Carolina, it became apparent to Williams that the president hadn’t lost his appeal. Indeed, in some counties, Trump did better Tuesday night than he did in 2016. At 9:44 p.m. Williams tweeted, “Damn, white supremacy is resilient.” As results trickled in, it became evident that neither candidate would be able to claim a quick and decisive victory. But to some Black Americans, muddled voting tallies signaled a clear victor: American racism...A critical voting bloc for Democrats who overwhelmingly rejected Trump in 2016, many Black voters felt the choice for 2020 was clear: A vote for the incumbent would be a vote in favor of racist policy and rhetoric. But even given the stakes — and following a summer that saw millions march for racial justice — the country overall was split roughly down the middle, a fact that several exasperated Black voters called “disappointing but not surprising.” “The impulse in this country for the status quo never ceases to amaze me . . . and on some level, that’s a strength — that’s how we get stability,” said David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School. “But that stability is a system of white supremacy and racial oppression.” In the last few months of the campaign, Trump capitalized on the fears of white suburbanites, with inflammatory talk of law and order and rising crime. Long before final results were set to be called in Michigan, Wisconsin, and several other key states, social media was already abuzz with lessons drawn from the close contest.

-

Push to Remove Racist Names Draws Support — And Backlash

October 26, 2020

For more than two decades, Black residents of Rhode Island have argued that the official name of their state, “The State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations,” connotes slavery and should be changed. It’s a “hurtful term” that “conjures extremely painful images for many Rhode Islanders,” said Democratic state Sen. Harold Metts, who traces his family lineage to a plantation in Virginia and is the only Black man in the Senate. Metts sponsored a bill to amend the state constitution to remove “Providence Plantations” from the official state name. Rhode Island voters will decide in November, but Democratic Gov. Gina Raimondo already has issued an executive order removing the phrase from official state documents, websites and paystubs. Citing the George Floyd killing in Minneapolis, Raimondo said Rhode Island must do more to fight racial injustice...Faneuil Hall, also called the Cradle of Liberty for the many historic events there, is owned by the city and has a visitors’ center operated by the National Park Service. Peter Faneuil, one of Boston’s wealthiest merchants in the 18th century, proposed a marketplace in 1740 and paid for the building. He was a slaveholder and slave trader. Renaming Faneuil Hall is “metaphor for addressing cultural racism in the city,” said Peterson, founder of the New Democracy Coalition, an advocacy group focusing on civic education and electoral justice. Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a Democrat, said in June he opposes the name change...To David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, “Keeping these names is a way of normalizing the horrors of our history.” Visitors to Faneuil Hall “don’t even know it’s named for a person. That’s how deeply buried our troubled past is,” Harris said in an interview. He co-wrote an essay calling for a public conversation about renaming Faneuil Hall but stopped short of endorsing a change. The headline erroneously said the authors were calling for a name change. “We said we need to have this conversation. By having a conversation, the public has a voice in the decision,” he said. “I don’t want to pretend it’s as important to change a name as to change a policy,” Harris said, adding, “but it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do both.”

-

Madison Park coach explores Boston gangs in documentary: ‘It’s all about trying to open eyes and save lives’

August 31, 2020

They say they are family, that they will die for each other. And so they do, young men in Boston street gangs who for decades have arrived at hospital emergency rooms, felled by gunfire. Some have worn tattoos that read like commentaries on the social and economic deprivations that have shaped their short lives. “Born to be hated.” “Dying to be loved.” “Death is nothing. But to live defeated is to die every day.” The images are “burned into my consciousness,” Dr. Thea James, the director of Boston Medical Center’s violence intervention advocacy program, says in a penetrating documentary film, “This Ain’t Normal,” about the causes of gang affiliations in Boston and the possible solutions. The film is produced by Dennis Wilson, an acclaimed history teacher, basketball coach, and football coach at Madison Park Technical Vocational High School in Roxbury, who for 40 years has witnessed and tried to curb the deadly toll of street violence. Wilson said he produced the documentary with a friend, Rudy Hypolite, to shine a light on the systemic and institutional racism they hold responsible for the long reign of Boston’s urban gang culture. Some of Wilson’s former student-athletes are among the dead. “It’s all about trying to open eyes and save lives,” he said... “This Ain’t Normal” won an Audience Choice Award at the Orlando Film Festival and has been presented twice at Harvard University, first by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, then as part of the Harvard Library’s “Anti-Black Racism Documentary Film Series.” David Harris, the institute’s managing director, said, “The film is a powerful antidote to the way people think about our young people and our communities. Every elected official should have to see it and ponder and wrestle with its lessons.”

-

Fanueil Hall name change needed

August 6, 2020

An article by Marty Blatt and David J. Harris: In light of the lynching of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter uprising, we call on the city of Boston to engage in the ongoing conversation, initiated by Kevin Peterson and the New Democracy Coalition more than a year ago, about changing the name of Faneuil Hall. Indeed, this would be consistent with the decision of Boston to remove the copy of the memorial, “The Emancipation Group,” which depicts a standing Lincoln and kneeling black man gazing up at him. If the statue of a figure as revered as Lincoln is being removed, how can we retain the name of Peter Faneuil, a local merchant who became one of the wealthiest men in the colonies buying and selling human beings. Although most of us are aware of the Atlantic slave trade originating in Africa, historian Jared Hardesty has documented that Faneuil’s ship, The Jolly Bachelor, was involved in trafficking enslaved people throughout the West Indies and into New England. This smaller scale, inter-American slaving, Hardesty argues, was the primary way Bostonians participated in the slave trade. Indeed, as a successful merchant, Faneuil also extended credit to other New Englanders engaged in the slave trade and was, as such, a financier of white supremacy. Does having paid for the building warrant retaining the name in perpetuity, when doing so maintains a place of honor and respect? We might well ask whether Faneuil actually paid for the building or whether it was purchased by the lives and freedom of those he transported and sold. Some argue that Faneuil Hall, whatever its origins story, has ironically become known as the cradle of liberty, a historic site whose name has become associated with abolitionists and suffragists who spoke there. In removing the name of Faneuil, so this argument goes, history is being erased. We would counter that by retaining the name of Faneuil, we in Boston do a great disservice to history by concealing his true past. Many visitors to Boston and many Bostonians have no idea that Faneuil was a slave trader.

-

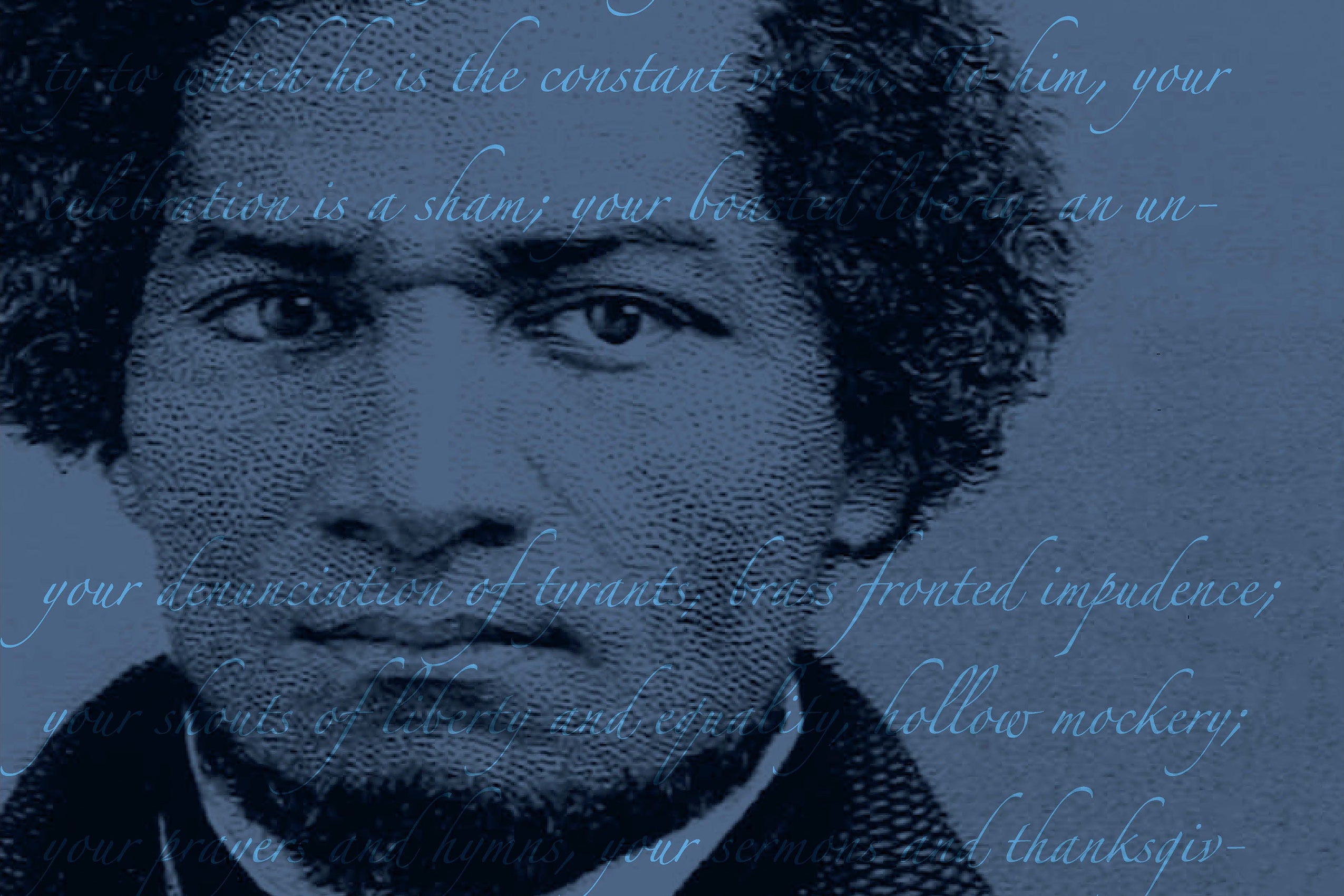

Reading Frederick Douglass together

June 30, 2020

In a July 2019 Q&A, David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, discussed the annual public reading of Douglass’ speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, virtual this year for the first time in its 12-year history.

-

The phrase ‘criminal justice system’ has to go

June 29, 2020

An article by David J. Harris: It is becoming increasingly clear that we, as a nation, have arrived at a crossroads. Between the coronavirus and the private and state-sanctioned lynchings of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd sandwiched around the white lives matter moment of Amy Cooper, we seem to be approaching a reckoning of sorts. That reckoning will be essential if we are to move forward from this place of pain and anguish. And any such movement will certainly require deep and broad reflection and action. An essential aspect of our reckoning will be interrogating the language we use to describe the social forces we confront. For several years I have been advocating that we eliminate the term “criminal justice system” from our lexicon. It is a term fraught with powerful negative associations and one that corrupts the meaning of justice. It is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine a system that begins with “criminal” as a pathway to anything but criminalization. As with breaking any habit, withdrawing from “criminal justice” can be painful. It is, after all, accepted as a term of trade. The phrase is used to capture a whole range of activities from policing to prosecution, from charging to conviction, from trial to sentencing and (mass) incarceration. On the front end it captures police, bail, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges. On the back end, it describes all who function within prisons, parole, probation. This is not an exhaustive list, but it makes the point: however dysfunctional it may be, it certainly has enough components to look like a system. But, let’s call that system what it is: a law enforcement system.

-

‘When I hear Black Lives Matter, I want to focus on the lives.’ After policing, a host of other systems await reform

June 26, 2020

Growing up in Roxbury, Feliciano Tavares’ family shuffled in and out of shelters and subsidized housing, seeking stability amid the turbulence of poverty. But Tavares’ precarious home life was a secret to his classmates and most of his teachers in Weston, an affluent, mostly white suburb west of Boston, where he went to school through Metco, the state’s voluntary integration program for students of color. Those years going to school in Weston, Tavares said, exposed him to the “full spectrum of the American experience,” one divided along unrelenting racial and economic lines, where white children in Weston have access to every resource and opportunity imaginable, and Black children like himself can’t walk to a well-funded school in their own neighborhood. “When I hear ‘Black Lives Matter,’ I really want to focus on the ‘lives’ part of that statement,” said Tavares, who is now 42 and raising his own son and daughter with his wife in Roslindale...Organizers, city councilors, and community advocates have criticized Mayor Martin J. Walsh’s proposal to reallocate 20 percent — about $12 million — of the police department’s ballooning overtime budget to a variety of social services as woefully inadequate. “If you took the entire police budget, it wouldn’t be enough of an investment in terms of what we need,” said David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice at Harvard Law School. He pointed to a detail from the 2017 Globe Spotlight series on race in Boston, which cited a jaw-dropping statistic: According to a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Duke University, and the New School, the median net worth for nonimmigrant Black households in the Greater Boston region is $8, compared with $247,500 for white families. “That is the reality of life in Boston,” Harris added. “It speaks to the scale of what we face.”

-

Institutional racism contributes to Covid-19’s “double whammy” impact on the Black community, Fauci says

June 24, 2020

Institutional racism in the United States contributes to the disproportional impact that the coronavirus pandemic has had on the Black community, the nation's top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, said on Tuesday. When asked about the racial disparities emerging amid the pandemic during the House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing on the "Oversight of the Trump Administration's Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic," Fauci responded that the Black community has been facing a "double whammy." Fauci noted that some Black adults may not be able to social distance if they are essential workers, and there is a disproportionate prevalence of underlying conditions within the Black community, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, chronic lung disease and kidney disease...The coronavirus pandemic has made it more clear than ever before that the United States needs to invest in communities -- especially in ways that could reduce health disparities, one expert on racial justice said last week. "I think we need to think about devoting more resources to addressing the issues that create the disparities and prevalence in susceptibility to coronavirus," David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, said on a Facebook Live discussion. "It's the way in which the institutional racism, for lack of a better word, seeps down into some very, very specific and particular differences in treatment," he said.Addressing racism and Covid-19 in a talk about inequities and policing on Thursday, Harris highlighted issues that have put Black communities at a disadvantage as the pandemic has gone on.

-

Rewriting history — to include all of it this time

June 23, 2020

Ninety-nine years after a mob of poor white people killed 150 to 300 African Americans and destroyed the “Black Wall Street” in Tulsa, Okla., the city again made headlines when President Trump announced he would kick off his re-election campaign there on Juneteenth — the day that marks the final end of slavery in the U.S. Although the rally was subsequently rescheduled for Saturday, Trump’s actions brought renewed attention to the 1921 massacre in Tulsa’s Greenwood District, a tragedy that generally has been overlooked in American history classes. This oversight, said participants in a Weatherhead Initiative on Global History webinar on Thursday, is emblematic of — and continues to contribute to — America’s racial divide...Smashing communities and burying their histories erases stories of Black success and possibility, the panelists said...Addressing “the disinvestment and what we’ve done to our cities,” David J. Harris, managing director of Harvard Law School’s Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice, which cosponsored the webinar, pointed out the ongoing repercussions. Most recently, he said, “COVID-19 has revealed how these disparities have caused great harm.” “We can never let up,” said Harris. “There’s no way forward until and unless we truly reckon with all of this history.”

-

Calls for social justice and police reform have gained momentum as unrest continues across around the world in the wake of the killing of George Floyd. These calls are intersecting with the coronavirus pandemic. As part of our regular series discussing the coronavirus crisis, The World's health reporter Elana Gordon moderated a live conversation with David Harris, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School.

-

Juneteenth in a time of reckoning

June 19, 2020

... To understand the significance of Juneteenth, a blending of the words June and 19th, we asked some members of the Harvard community what the holiday means to them. ...David Harris, Ph.D.’92, managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School: "Juneteenth is a defining day. However empty the promise of freedom often appears to have been, Juneteenth has remained a day uniquely celebrated by the descendants of the formerly enslaved." ...Kenneth Mack, Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law at Harvard Law School; affiliate professor of history at Harvard University: .".. We commemorate Abraham Lincoln in various ways, but we don’t have a national commemoration of the triumph over slavery, which has to be one of the most important moments in American history. One should consider Juneteenth in that context. The best case to be made for Juneteenth would be as a commemoration of both the legacy of slavery and the success of the movement to abolish formal slavery in the United States."

-

‘Juneteenth is a day of reflection of how we as a country and as individuals continue to reckon with slavery’

June 18, 2020

Tomiko Brown-Nagin spoke with Harvard Law Today about the history of Juneteenth and its particular relevance more than 150 years later.

-

After the protest…what next?

June 12, 2020

An article by David Harris: First, and essentially, we must reckon with what our history has wrought. As difficult as such a reckoning will be to define, indicators will reveal the extent to which we have succeeded. In order to facilitate the process, we must acknowledge a foundational point: “We the People” has never included all of us. That cannot be subject to debate. Once we acknowledge this defining exclusion, we can trace the myriad ways in which having denied large groups of people, notably African Americans and Native Americans, the most basic rights of membership and participation — the qualities of citizenship — has diminished life chances for individuals and communities. Understanding the real, ongoing harm from policies and practices that have differentially distributed access and opportunity, state violence, and deprivation will open our eyes to avenues for repair and restoration. We must rethink our notions of justice, as well. Our current coupling of criminality and justice locks us into a fixation on punishment in lieu of a system of justice. I understand justice as being made whole, which promotes practices that center on health and well-being of all residents, and whole communities, as the hallmarks of safety. Another more tangible indicator of our progress on the pathway to reckoning will be whether we not only hear and empathize with what people who have suffered for decades are saying, but act in truly responsive ways. As people are taking to the streets at great risk to themselves to decry the institutionalized racial violence perpetuated by policing, promoting legislation that bans chokeholds is tone deaf.

-

What if we eliminated the police?

June 5, 2020

An article by David Harris: I hate the PO-lice. This is not an easy thing to admit and will certainly generate a great deal of heat, but it is past time to do so. To be clear from the beginning, this hatred is not directed at individuals, whether rank and file or leadership. It is directed at the institution and practice of policing in the United States, born as it was from the practices of slave catching, which has served as an instrument of social control over black people for far too long. So, I hate the policing. I have to keep saying it. It’s more important than repeating the name of someone who has been killed or any other chant we might invoke in protest. It conveys a truth, hard to come by, but once arrived, so very cathartic. It is a complicated admission and it actually feels like a confession. I have always told my son “hate is a strong word,” and urged him to use it sparingly. Sunday night when he returned from marching and protesting on the streets of Boston and we were watching the policing of the city on television, I had to say it out loud, though in a muted voice. “I hate the police,” I whispered. My son has grown up in the era of cellphones and social media. He has been bombarded but also socialized by social media reports of police atrocities. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, we have talked about policing at length and in those conversations, informed by his couple years of college, including a course on Red Summer of 1919, we talked about police abolition. I told him how happy I was to know that he had been listening to me for all the years I have been telling him police are not a natural phenomenon, that society existed and survived for millennia without them.

-

Structural racism is the real pandemic

May 19, 2020

An article by Monica Cannon-Grant and David Harris: As the death toll mounts daily from COVID-19, so do the headlines and data documenting its disparate impact on communities of color, especially black people, immigrants, native people, poor people, and those living at the intersections of these identities. The impact of COVID-19 tells a tale of the “web of disadvantage” spun from decades of disinvestment in, and disregard for, poor communities of color. Structural racism is the pandemic; COVID-19’s disparate impact is just a symptom of a long-festering and deadly virus. The disparities and injustice being exposed and underscored by the unequal spread of the novel coronavirus are no revelation. Our people have been living through the pandemic of racism for centuries—too often ignored or unseen as many enjoyed health and prosperity, now suddenly threatened. We won’t dwell on the reasons for the disparities: poverty-stricken communities lack access to adequate personal protective equipment; poor communities of color are overburdened with preexisting social conditions of air pollution and environmental toxicity and food deserts and inequities in healthcare; social distancing is a privilege denied to “black and Latino workers overrepresented among the essential, the unemployed, and the dead.” In recent weeks as we read about the surge, flattening the curve, protests over supposed infringement of rights, the threat to the economy, and additional billions in relief, we’ve seen more of the same on the streets of Boston. Our people are hurting. Our people are dying.

-

She Stole Something While Struggling With Heroin Addiction. Cops Turned Her Into A Facebook Meme.

November 8, 2019

On May 31, Meghan Burmester became a meme. She was featured, along with four other women, on the Harford County Sheriff’s Office “Ladies’ Night” Facebook post for alleged theft under $1,500. “Oh yes! It's Ladies' Night here in Harford County!” the post said. “This month we are running our summer special - turn yourself in, and get a free stay at the Harford County Rock Spring Road Spa (a.k.a, Harford County Detention Center). Sorry, no pedicures, manicures, facials, massages, spa services included (or available).” The Maryland department’s “Ladies’ Night” Facebook posts, which feature a handful of women who have open warrants against them usually for alleged theft or traffic- or drug-related offenses, are a big hit with its 55,000 followers...“If you looked like one of the people being mocked by the police department, what kind of confidence would you have in police?” David Harris, the managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School and a civil rights advocate, told BuzzFeed News. He said the Houston Institute is in the process of recruiting more people to review offensive social media posts by law enforcement agencies and to identify potential relations between agencies’ Facebook posts and possible racial disparities in how they use force and conduct arrests or traffic stops.