Alumni Spotlight: Transforming legal education in Mexico

Marcela Barrio-Olivas LL.M. ’01 and Luis Perez-Hurtado LL.M. ’01 have created a research-focused center to train law teachers and other legal professionals

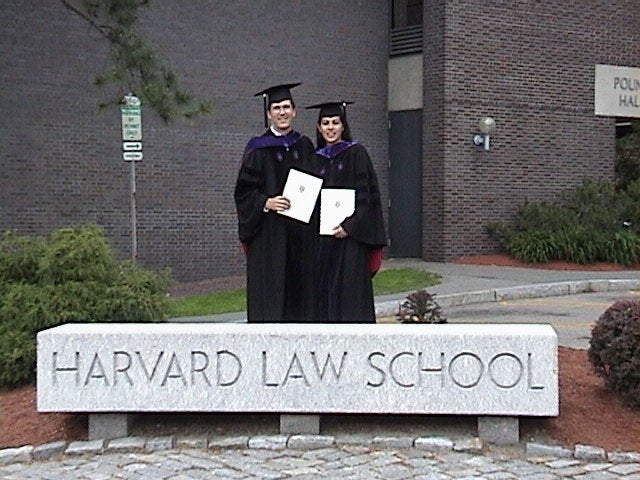

They were on their honeymoon when Marcela Barrio-Olivas LL.M. ’01 and Luis Perez-Hurtado LL.M ’01 learned they had both been admitted to the LL.M. Program. A few months later, they left their jobs in Monterrey, Mexico, and arrived at HLS, eager to plunge into coursework that they hoped would help them in their intended careers as corporate lawyers.

But “planning is one thing, and life is another,” observed Marcela. Thrilled with the freedom to choose from a wide array of courses and extracurricular offerings, she opted to expand her intellectual horizons and took courses in subjects such as American Legal Education and International Trade Law that were not directly relevant to her original career aspirations.

Meanwhile, Luis – who, along with his legal practice, had also been a lecturer at the Universidad de Monterrey Law School before coming to HLS, and who had long had an interest in ADR – was coming to realize that his heart was in education, and that his dream was to lead a research center working to change the way people and organizations in Mexico resolve their disputes. In reaching this conclusion, he was inspired as much by what he observed at HLS about academic research and institutional collaboration as by the courses he took in negotiation and ADR.

Lessons from HLS

Beyond the problem-solving approach in U.S. legal education that they found so novel and exhilarating, Marcela and Luis were amazed to see how HLS faculty were engaged in research and activities that did not just revolve around historical or theoretical issues (as was the practice in Mexico) but were also aimed at addressing current real-world problems. Luis also marveled at the collaboration between luminaries in the field of negotiation on the Harvard faculty and those from MIT, Tufts, and other universities, working together on joint projects at the Program on Negotiation that were advancing the field of negotiation.

Separately and together, Marcela and Luis took everything they learned at HLS to heart. And by the time he graduated, Luis knew for certain that he wanted to pursue a career in law teaching and scholarship. He also realized that in order to promote the kind of law teaching he’d like to see in Mexico, he would need to figure out how to train faculty to impart both knowledge and practical skills in their teaching; develop appropriate teaching materials; and induce Mexican institutions to work together in a collaborative manner – ideas and concepts he would further elaborate and refine during his subsequent JSD studies at Stanford.

Applying what they’ve learned

When they returned to Monterrey in 2008, Luis and Marcela founded the Center for the Studies on Law Teaching and Learning (CEEAD), an independent nonprofit whose mission and activities are the embodiment and fruition of those early ideas about teaching, research, and collaboration. From its humble beginnings (when Marcela and Luis did all the work with no pay and financed their expenses with loans), to its current staff of more than 90 salaried professionals engaged in dozens of projects, CEEAD has steadfastly pursued its goal of transforming legal education and the practice of law in Mexico, applying a two-pronged approach of conducting rigorous research and using that research to inform and develop programs and initiatives to train faculty and other legal professionals.

One early project was the development of a model curriculum for a law degree at schools catering to indigenous populations. Such schools are typically small institutions with few resources, yet they play an important role in making Mexican legal education more accessible and affordable to underserved communities, which otherwise have very limited options to pursue higher education. Nevertheless, periodically there would be calls to close such schools for failing to meet certain standards. Rather than letting them fail, Marcela and Luis saw it as an opportunity to help these schools achieve higher standards and better practices by developing a model law degree curriculum tailored to meet the needs of indigenous communities. For this project, Marcela and Luis even moved their growing family to Chiapas for four years, so they could better understand the needs and conditions faced by one of the largest indigenous populations in Mexico as they worked to build this model. To date, the reference model they developed – which aims to train competent, ethical, and socially responsible lawyers – is in use at 10 indigenous universities across Mexico.

Another project dear to their hearts is one inspired by the spirit of collaboration among faculty from different institutions that Luis first observed at Harvard’s Program on Negotiation. Although law schools in Mexico do not regularly collaborate across institutional lines, Luis nevertheless managed to persuade faculty members from the four top law schools in Monterrey (one public and three private universities) to jointly teach a course that is open to select students from each of the four institutions. This interinstitutional course, on ADR, was the first of its kind in Mexico; it was so successful that it has led to two further interinstitutional courses, one on IP and another on environmental law. While this project began only three years ago, Luis is hopeful that it will generate many fruitful intellectual as well as social exchanges, not only among the collaborating faculty but also among the students from the four institutions, who come from distinctly different social and economic backgrounds.

The most important lesson Marcela and Luis learned at HLS – the impetus to apply rigorous academic research to help solve current problems – is a theme that runs through all of CEEAD’s work, and nowhere is this more evident than in the two projects that were developed in the aftermath of the 2008 amendment of the Mexican Constitution. The amendment transformed Mexico’s criminal justice system to follow a more adversarial model, which brought about a fundamental change in the knowledge and skills needed to practice criminal law.

Transforming legal education

Seeing in this an opportunity to make a real impact on legal education in Mexico, Marcela and Luis – together with their colleagues at CEEAD – began working on a project to help law schools adapt to the new criminal justice system, not merely by adding a few new courses or modifying the content of existing ones, but by also developing teaching manuals and case materials and instituting training programs for faculty on active teaching techniques. In addition, they developed guidelines to reform the curriculum (adaptable to the particular educational model used by a law school), standardized tests to evaluate how well students were learning, as well as institutional assessments to identify problems in the implementation of these academic changes. To cap it off, they made everything free and easily accessible online.

To date, the materials developed for this project have been downloaded almost 200,000 times, and CEEAD has trained criminal law professors from 994 law schools from every Mexican state, with the standardized tests helping to improve student capacities on this topic. With the experience gained from this project, CEEAD has gone on to develop similar materials and training programs in response to constitutional reforms in the areas of human rights, indigenous law, and labor law, as well as for topics relevant to the practice of law, including ethics and professional responsibility, gender perspectives, and well-being. In all, more than 11,000 faculty, trainers, and executive staff from approximately 2,000 law schools and legal training institutions across Mexico have taken a training course with CEEAD, have participated in one of their events, or are using their teaching materials.

Transforming legal practice

Turning their attention to practitioners, CEEAD worked to help state Attorney General offices develop a process to assess and certify local prosecutors who must implement the changes resulting from the constitutional amendments in criminal law and practice. This process takes anywhere from 12 to 18 months to complete, and includes standardized assessments with multiple choice options, similar to those used in bar exams in the U.S.; it also entails evaluations of actual prosecutorial performance based on videos of criminal trials and court documents to gauge whether participants have mastered specific elements of criminal procedure. Those who complete the process receive an official certification, based on which local Attorney General offices can assign them to cases and tasks where their training is directly relevant. To date, CEEAD has administered this process for almost 9,500 local prosecutors from 28 of the 32 Mexican states, representing 70% of all local prosecutors.

A serendipitous lesson

Looking back on where they started and how far CEEAD has come, Marcela and Luis credit the writing and argumentation skills they acquired from working closely with their LL.M. paper supervisors for helping them write many successful grant applications. Over the years, CEEAD has obtained multi-year grants from major international development organizations including the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives, the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights, the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, USAID and the U.S. State Department, and its annual budget currently exceeds 4 million dollars.

The HLS Network

Through their LL.M. classmates, some of whom have played key roles in publicizing CEEAD’s work in other countries, Marcela and Luis have developed strong connections with research centers, NGOs, law schools and even law firms around the world. Philipp Dann LL.M. ’01, now a professor of public and comparative law at the Humboldt University of Berlin and editor of the World Comparative Law/VRU Journal, has invited them to write about the impact of international funding on legal education in the global south for a forthcoming issue of the journal. And Javier Rodríguez LL.M. ’01, now a partner in the Barcelona office of the international law firm Cuatrecasas, is working with them to set up internships at the firm’s Mexico City office for outstanding law students who have distinguished themselves during their participation in CEEAD programs and activities.

CEEAD’s work has also been facilitated and furthered by HLS alumni friends closer to home (e.g., Gerardo Puertas Gómez LL.M. ’84 and Fernando Villarreal Gonda LL.M. ’90 at Facultad Libre de Derecho de Monterrey, and Gregorio Canales LL.M. ’86 and Mario Zambrano Ábrego LL.M. ’02 at law firms in Monterrey). In addition, Professors Imer Flores Mendoza LL.M. ’96 (Senior Researcher at UNAM’s Legal Research Institute), Helena Alviar García SJD ’01 (formerly Dean of the Universidad de los Andes law faculty and currently a professor at Sciences Po in Paris), and Isabel Jaramillo Sierra SJD ‘07 and Diego López Medina SJD ‘01 (both on the law faculty of the Universidad de los Andes) have each attended and spoken at CEEAD’s annual congresses on legal education.

Looking ahead

In 2023, CEEAD will celebrate the 15th anniversary of its founding with a variety of events. With that milestone on the horizon, Luis has been busy working on a strategic plan to continue the consolidation of the organization while also looking forward to the designation of a new Director General, after which he will step down from his current post but remain as President of the Board of Directors. He plans to take on a more strategic role in securing funding, building more alliances, and focusing on special projects. Marcela also plans to step back from her current role as CEEAD’s head of special projects but will remain as a member of its Board of Directors. And both Marcela and Luis are looking forward to seeing their classmates again at their 25th-year reunion – this time in Cambridge for sure!

Student Spotlight: An S.J.D. at long last

First-year S.J.D. student Deyaa Alrwishdi finally embarks on a dissertation project postponed by the war in Syria and years of activism

Growing up in Homs, the third-largest city in Syria, Deyaa Alrwishdi enjoyed rhetoric and reciting poetry by the dissident lawyer poet Nizar Qabbani. So his mother, Zaeda Majar, an educator whom Deyaa cites as the most influential person in his life, encouraged him to pursue a career in law. But Deyaa, whose family had little means, particularly after his parents divorced when he was 10, was primarily focused on finding a job to earn money. With help from his uncle, he obtained a civilian administrative position with the Syrian Military Construction and Establishment Institute (MCE), a government agency similar to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that monitored construction projects. He also enrolled in a law program at Damascus University Open-Learning Department, largely to appease his mother, but found his first year of study so uninspiring that he skipped most of his exams. Over the next few years, however, he developed a true intellectual interest in law and decided to work toward pursuing doctoral studies in France. But circumstances intervened.

Protests in the Arab Spring

After Deyaa finished his law studies in 2010, he embarked on mandatory professional training with a well-respected Homs lawyer while maintaining a full-time role with his government employer. Then, in 2011, the Arab Spring movement spawned protests in Syria. Having long been critical of the government, Deyaa was immediately caught up in the action. Not only was Homs a center of protest activity in Syria, but Deyaa’s working class neighborhood, Bab al-Sebaa, was the epicenter of the protests and unrest in Homs. Deyaa and his siblings were among the people who were playing a key role in coordinating the protests and facilitating coverage by foreign journalists.

Protests in Homs quickly became violent. Deyaa participated in a number of protests – and witnessed others – in which the military and intelligence authorities shot protestors and engaged in other forms of brutal behavior. Residents of Deyaa’s neighborhood started to return fire when the military raided the neighborhood. On one occasion, Deyaa’s mother urged him not to return home because of the intensity of the conflict. By the time he was able to re-enter the neighborhood, he found streets full of overturned cars and learned that nine of the residents had been killed.

Even though his focus was on property law, Deyaa wanted to document the human rights violations and atrocities that were happening, and he wanted to help protestors and other political prisoners who had been detained (and, in many instances, tortured) by Syria’s multiple intelligence agencies. Relying on his growing government and legal connections, he obtained lists of the people who had been referred to the prosecution court after having been interrogated, and he filed bail applications on their behalf. By August of 2011, Deyaa had decided to start a network of lawyers across Syria doing similar work.

In the meantime, the Free Syrian Army, formed by defecting Syrian army officers opposed to the Assad government, started to gain ground, taking over numerous villages and towns in northern Syria. Deyaa wondered how those areas would operate in the absence of functioning government institutions. In spite of the conflict, some measure of day to day life would continue, necessitating municipal structures and legal systems, schools, and similar institutions.

Focusing on the rule of law

As the conflict progressed, Syria’s legal system and courts began to shut down. Deyaa shifted his focus from bail applications to questions of governance and rule of law, and to providing assistance to residents of Homs who had been forced to flee to Damascus. Significantly, Deyaa had been issued a Ministry of Defense ID to enable him to move freely through checkpoints while working on projects with the MCE. As a result, he was able to travel in and out of Bab al-Sebaa, and internally within the country, often without being searched. He stockpiled diapers and baby formula in his government apartment in Damascus and delivered them, along with food and medication, to the displaced residents of Homs.

Although he had been using a nom de guerre, in May 2012, he was cautioned by a friend that military intelligence was aware of his activities. Later that summer, he tried to visit family in Lebanon but learned that he was on a banned list and no longer permitted to leave the country. He was instructed to report to military intelligence, but managed to get away without doing so. Instead, he tried to leave the country illegally on multiple occasions with the help of activists in the Homs countryside but did not succeed. Ultimately, he obtained permission to study in Lebanon in November 2012, but flew to Turkey immediately upon arrival, before his name could be circulated to Lebanese authorities. From Turkey, he was able to enter liberated northern Syria, where he organized a meeting of his lawyer network, now comprised of approximately 150 Syrian lawyers. The meeting – to discuss legal issues and governance for liberated parts of Syria – was broadcast on the Al Jazeera and Al-Arabiya news outlets and received even more attention when its internet connection was interrupted mid-meeting by a nearby airstrike. Though the military operation was unrelated to the meeting, initial reports stated that the military had attacked the conference. In the course of the news coverage, Deyaa’s identity was publicly revealed.

After the meeting, Deyaa returned to Turkey and established an office for his network of lawyers, the Free Syrian Lawyers Association, near the Syrian border. Shortly thereafter, he was approached by an official from the U.S. Department of State, who suggested that he seek funding from the State Department’s Middle East Partnership Initiative. He received a substantial grant to fund his organization, but in May 2013 was compelled to relocate after the building in which his office was located was targeted in a terrorist bombing. Deyaa was fortunate to escape with minor injuries, but nearly 50 people died in the attack.

Using the State Department grant, Deyaa’s organization partnered with human rights organizations, such as the New York-based Witness, to train Syrian lawyers to use cameras to gather evidence. It also worked with local lawyers to create a legal framework to register cars brought in to northern Syria from Eastern Europe and northern Turkey. One question that arose was whether a person who purchased a car registered by a non-state authority in liberated northern Syria would still own it if Assad’s government regained power in the region. The question seemed relatively simple, but after researching it, Deyaa realized that there was no clear answer.

Fellowships and asylum

After some time, Deyaa’s State Department contact urged him to apply for a Leaders for Democracy fellowship for emerging Arab and Middle Eastern leaders at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He received the fellowship and at the end of the program completed a practicum with the ABA Role of Law Initiative in Washington, D.C. After that ended he found himself with an expired Syrian passport and apprehensive about trying to return to Turkey, so he decided to apply for asylum in the U.S.

The period that followed was incredibly stressful. Deyaa had no work authorization and no money. He lived in a low-rent apartment that he could barely afford. He had no furniture and for months did not even have a blanket. He occupied his time by walking back and forth from Northern Virginia to Washington D.C. to attend Middle East-focused events at major think tanks. He worked on improving his English by writing reports on the think tanks’ publications and watching Senate hearings on C-SPAN.

“I was in the worst psychological state in my life because I had graduated from law school and built a career in Syria. I had just become something. I was making much more money than my mother who had worked for the government for 40 years, and then I had to start completely over, with nothing.”

Over time, Deyaa began to develop connections through the think tank events. He received speaking invitations and formed relationships with journalists. He revived his plans for graduate study and decided to apply for the PILnet Fellowship (for public interest law work) at Columbia Law School. While waiting to hear from Columbia, his work authorization came through. Deyaa started delivering pizza to earn money, but the car he was using was not registered in his name. On one occasion, a delivery to a U.S. military facility nearly landed him in jail – he was surrounded by armed guards but ultimately released with tickets for driving without a registration and for disobeying a police officer. Concerned that the tickets might jeopardize his asylum application, he challenged the tickets in court and obtained a dismissal.

The Columbia fellowship came through. He moved to New York, where he lived in the International Student House and performed poetry in Arabic and English. He participated in a wide range of activities, made good friends, and improved his English. “I started to feel human again,” he recalls. PILnet nominated Deyaa for Stanford Law School’s Rubin Family International Human Rights Award, which he received in 2016.

Pursuing an LL.M.

By that time, he had decided to pursue an LL.M. degree. He set his sights on the American University Washington College of Law (WCL) and was admitted to its LL.M. program with a full-tuition scholarship. To make ends meet before the program started, he started to drive for Uber, enjoying the opportunity to discuss politics with passengers in the Washington, D.C. area.

At WCL, Deyaa developed close relationships with several faculty members, especially Rebecca Hamilton J.D. ’07. He started thinking seriously about pursuing an academic career. But just after graduating from the LL.M. program in 2017, Deyaa learned from a cousin that his father had been killed by ISIS, leaving behind a wife and three children under the age of 14. He grieved his father’s death and felt financially responsible for his father’s family. “I was totally lost. Should I try to retaliate with activism or stay in academia?”

Together with friends from WCL, Deyaa established the Center for Rule of Law and Good Governance to help structure the work of NGOs in Syria. In 2018, the organization held a Syria Justice Conference in Istanbul, but Deyaa was the only one of his colleagues who could not attend because was unable to leave the country. He was nonetheless encouraged once again to apply for funding from the Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, and received a $1.8 million grant for a project involving advocacy, accountability, and psychosocial support for victims of sexual violence in Syria, the Syrian Initiative to Combat Sexual and Gender-Based Violence, hosted and supported by WCL. Deyaa was also appointed as an adjunct faculty member at WCL. He developed a class on “Innovative Lawyering in Times of Change” and then branched out further to develop a legal education program for lawyers whose legal education had been interrupted by conflict, as well as activists interested in documentation. Three of the four courses were taught bilingually in English and Arabic.

A dream no longer deferred

Though he was flourishing at WCL, Deyaa’s mentor encouraged him not to forget his dream to pursue doctoral studies. Recognizing that the schools where he wanted to study admitted S.J.D. candidates almost entirely from their own LL.M. programs, Deyaa applied and was admitted to a handful of LL.M. programs, including Harvard’s. Hoping to study with Professor Gabriella Blum LL.M. ’01, S.J.D. ’03, Deyaa enrolled at HLS in the fall of 2021. His gamble paid off. Not only did Professor Blum serve as his LL.M. paper supervisor, she also later agreed to supervise his S.J.D. project, and Deyaa was admitted to the S.J.D. program in June of 2022. This fall, he has commenced the doctoral studies he first contemplated roughly 15 years ago, on a topic stemming from his experience with the Free Syrian Lawyers Association: determining when and under what circumstances a non-state actor’s exercise of government functions (e.g., issuing marriage licenses, proof of identification, or property deeds) in situations of an incumbent government’s failure such as armed conflicts or other emergencies should be recognized as a matter of law. He hopes that the project will demilitarize the lives of civilians during armed conflicts by introducing a legal framework to support their daily transactions and give them the legal protection and sense of stability that he himself has been pursuing for years.

LL.M. Profiles

Srujana Bej (India)

Srujana Bej is an aspiring academic from India interested in critical caste studies and spatial justice. She has worked as a researcher investigating the treatment of marginalized communities in India’s criminal justice system and the impact of shrinking civic spaces on intersectional feminist organizing. She’s also been an advocate for the provision of and equitable access to play spaces. “I spent some time volunteering at a government residential school where most students were from nomadic tribal communities that have been forced to adopt sedentary ways of life. I was shocked to find that the children had no access to play space in their school, and realized that this mirrored the historical enclosure of their communities. I began to question how caste and geography shape identity, agency, and every aspect of day-to-day life.” Srujana plans to return India to teach at a public university and focus on the ways in which urban regulation and land ownership perpetuate caste power.

Anderson Javiel Dirocie De León (Dominican Republic)

Anderson Dirocie is an international and human rights lawyer from San Juan de la Maguana, a small city in the Dominican Republic. His single mother, Diamire De León, sacrificed and saved to support his studies and Anderson took advantage of every educational opportunity he could, traveling to Santo Domingo to take special classes, to New York for Model UN and to Paris to learn French. He studied law in the Dominican Republic and the Netherlands and worked on human rights issues on three continents, most recently as a fellow with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights at its Rapporteurship on the Rights of LGBTI+ persons. “Even when I was in the closet, I was a vocal advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, but I was afraid that if I came out in the Dominican Republic I’d be devalued professionally. Getting into Harvard made me feel safe enough to do so.” Anderson’s goal is to become a well-rounded international lawyer who can work for change in his country, his region, and globally.

Min Ryeoung Lee (South Korea)

Min Ryeoung Lee is a judge from South Korea spending the year at HLS with her husband and two young children, aged 3 and 4. As a junior judge, Min Ryeoung presided over civil enforcements, insolvency matters, and family law, instituting mediation proceedings in a number of cases. In the longer term she hopes to have a chance to work at the Korean Supreme Court. Since her experience has mostly been with bench trials, she is looking forward to taking Professor Nesson’s JuryX Workshop during the Winter term. “I love the learning environment at HLS, where we are encouraged to explore and take risks.” Outside of her academic work, Min Ryeoung has enjoyed organizing lunch talks with local judges and taking ballet classes with dancers from the Boston Ballet together with her J.D. student host, Nikol Tang.

Jakob Tschachler (Austria)

Jakob Tschachler got his start teaching criminal law at the University of Vienna before transitioning to a government career. Before coming to HLS, he served as deputy chief of staff for Austrian Federal Justice Minister Alma Zadić. “Working in politics is very intense – there’s no rush like it. And seeing the way laws are made changes how you look at practicing law.” As an LL.M. student, Jakob has particularly enjoyed looking at how economics, history, and political science can inform decisions about the law. He is also spending an hour each day working on his first novel, a thriller.

Eyram Homenya (Ghana)

Eyram Homenya is a corporate lawyer who grew up on the campus of the University of Ghana, where her father worked. She later decided to study law there to follow in her grandfather’s footsteps. Before coming to HLS, she worked for N. Dowuona & Company in Accra on all aspects of corporate deals. Her coursework at HLS has made her more curious about how deals work in the U.S. She hopes to spend some time working in M&A at an international law firm in the U.S. before returning to Ghana, and in the long term would like to start her own law firm. “The real highlights of Harvard are the people. It’s been beautiful to see how different people from different parts of the world at all stages of their careers have come together into one space — I’ve developed close-knit friendships with both LL.M. and JD students.”