David H. Souter ’66, retired associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, died peacefully at his home in New Hampshire on May 8. He was 85.

Appointed by President George H.W. Bush in 1990, Souter retired from the Court in 2009, after serving more than 19 years.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79, in a statement announcing Souter’s passing, said: “Justice David Souter served our Court with great distinction for nearly twenty years. He brought uncommon wisdom and kindness to a lifetime of public service.”

“We are saddened by the loss of Justice Souter and grateful for his decades of honorable public service,” said Harvard Law School’s Interim Dean John C.P. Goldberg, who served as a law clerk for Justice Byron White during Souter’s third year on the Court. “For all his extraordinary accomplishments, he was unassuming — it was never about him and always about the law. He loved his time at Harvard College and Harvard Law School, and we were fortunate that he returned to campus often over the years to share his wisdom and gentle humor with our community.”

Souter was among “the most consistent, principled justices ever to have sat on the U.S. Supreme Court in its 235-year history,” wrote Harvard Law Professor Noah Feldman, in a tribute in Bloomberg Opinion.

“His jurisprudence was steeped in the value of precedent and the gradual, cautious evolution of the law in the direction of liberty and equality,” Feldman noted. “A New Englander to the core, he said what he meant and meant what he said. At a moment of unprecedented threat to the rule of law, Souter’s career stands as a model of judicial strength and resilience tempered by modesty and restraint. If the court follows his example, the Republic will survive even the serious dangers it is facing now.”

Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and former dean of Harvard Law School, said she most cherished Souter’s “genuine kindness, astonishing humility, perpetual curiosity, and steadfast friendship.”

Echoing in her mind, said Minow, were comments Souter made during a 2013 visit to Harvard Law School when he joined Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and a panel of constitutional experts for a daylong symposium titled “Civics Education: Why It Matters to Democracy, Society, and You.” At the event, Souter said that binding the nation together is at the heart of the value system outlined in the Constitution, “a value system about how to use power and distribute it and limit it, and a value system that reflects a shared conception of human worth. That value system is the counterpoise to the divisive tendencies that are so strong. Civic ignorance is the defeat of that value system.”

His long view of what really matters, and his tempered optimism, remain powerful inspirations, said Minow.

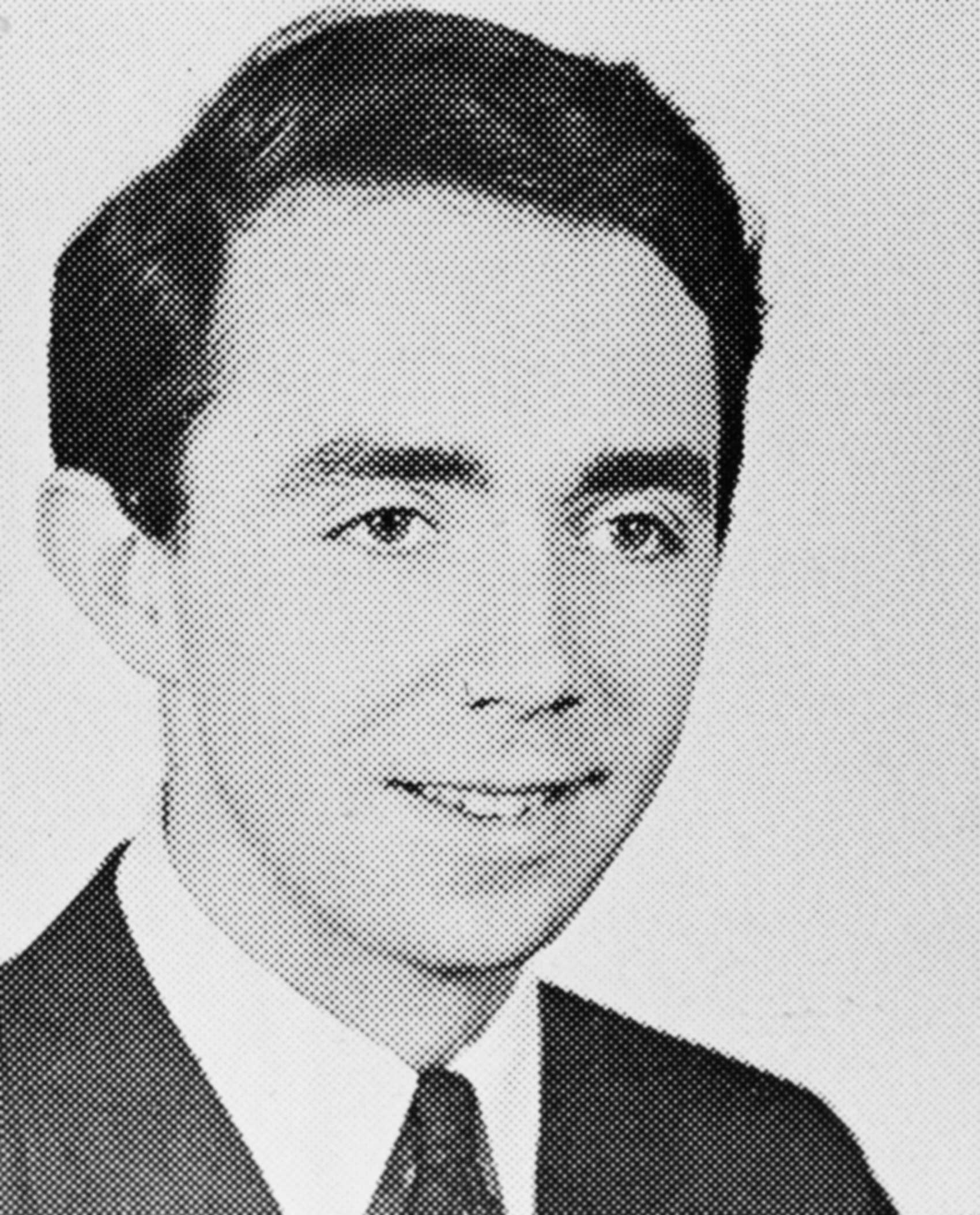

Born in 1939 in Melrose, Mass., on Constitution Day, Sept. 17, Souter grew up on his family’s farm in Weare, New Hampshire. He earned an A.B. from Harvard College, before serving as a Rhodes Scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford, where he received an A.B. in jurisprudence and an M.A. in 1963. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1966.

Souter spent his early career working in New Hampshire. He was an associate at Orr and Reno, in Concord, for two years, and then served as an assistant attorney general and deputy attorney general before being appointed as the state attorney general in 1976. In 1978, he was named a judge on the Superior Court of New Hampshire, before being named an associate justice of the state’s Supreme Court in 1983, where he served for seven years.

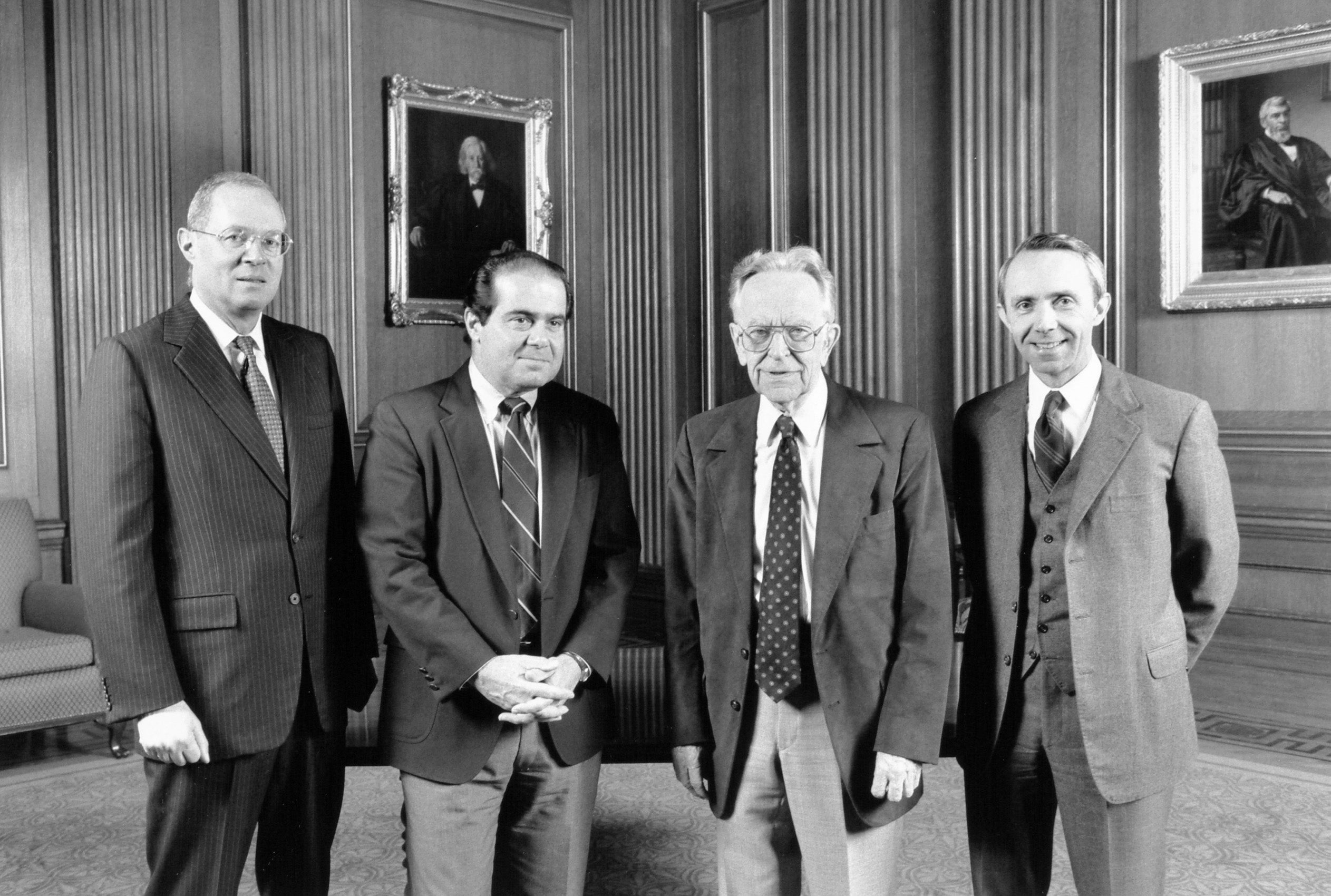

In May 1990, Souter was unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, in Boston, where Stephen Breyer ’64, the current Byrne Professor of Administrative Law and Process at Harvard Law School, then presided as chief justice.

Less than two months later, President George H.W. Bush would tap Souter for the U.S. Supreme Court. Breyer joined Souter on the high court, after being appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

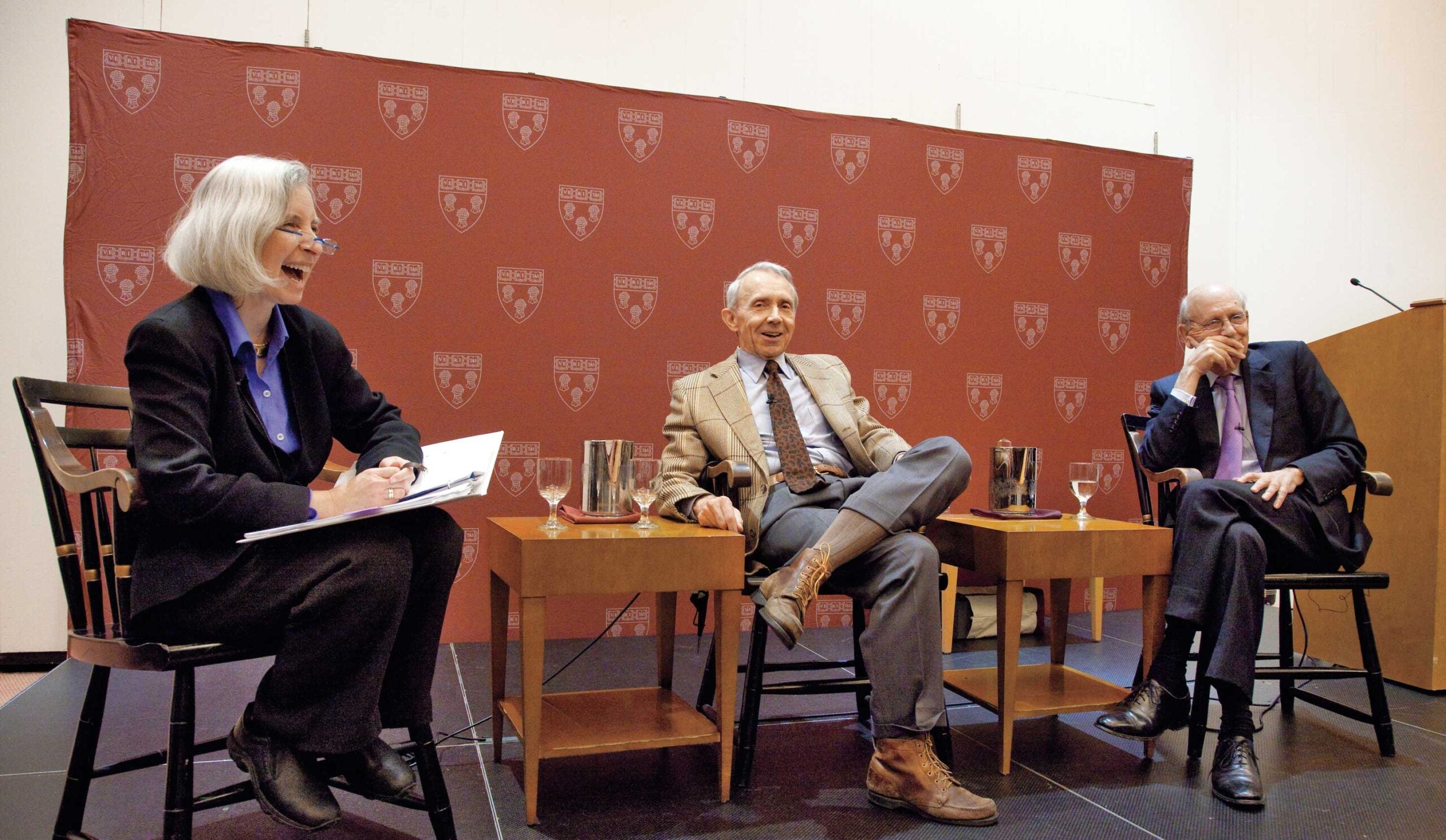

“David Souter and I served together on the Supreme Court for 15 years. For me that was a great privilege,” said Breyer. “He was a great judge. He was intelligent. He had a good sense of humor. He was a thoroughly decent person. He thought mostly not of himself but of the people the Constitution will serve. The judges will miss him, the lawyers will miss him, the country will miss him, and I will miss him very much indeed. He was my friend — my very good friend.”

Their easygoing friendship and good humor were on full display during a 2011 Harvard Law reunion event, when both participated in a “Conversation with the Justices,” moderated by then Dean Martha Minow. Recalling their time together on the First Circuit, Breyer kidded that Souter didn’t do much work; Souter responded that Breyer wasn’t a very efficient boss.

During that event, Souter relayed a swashbuckling story from his law school years, when he and a friend engaged in a fencing duel one evening, with a sword that had been gifted to Souter by a girlfriend. After Souter was cut during the fight, he said, a group of “well-oiled” students accompanied him to health services, which at the time overlooked “a venerable restaurant named Elsie’s.” Souter, spying Elsie’s, declared he would treat his friends to cream cheese and caviar, and he sent a freshman to get the food, at which point, he said, they were all kicked out of health services.

Laurence Tribe ’66, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor, Emeritus, who graduated with Souter in the Harvard Law School Class of 1966, hailed his fellow classmate’s approach to judging: “Conservative in style and inclination, Justice Souter moved gradually leftward in his constitutional jurisprudence as he encountered from his seat on the Supreme Court the difficult realities and inequities of life. In the end, he proved to be a great jurist, one whose intellectual and moral integrity remained uncompromised as the circumstances of a polarized Court would have tempted a lesser soul.”

After stepping down from the Court in 2009, Souter was the principal speaker at Harvard’s 359th Commencement in 2010, when he also received an honorary doctor of laws degree. In his 30-minute address, Souter took aim at what he termed the “fair reading” model of constitutional analysis as simplistic and prone to “discourage our tenacity … to keep the constitutional promises the nation has made.” Such a black-and-white approach, he argued, “fails to account for what the Constitution actually says, and fails just as badly to understand what judges have no choice but to do.”

Instead, he said, judges interpret the U.S. Constitution beyond a “fair reading” of its plain language. Because the judicial interpretation of facts can change over time, judges have to “understand their … meaning for the living.”

“If we cannot share every intellectual assumption that formed the minds of those who framed the charter, we can still address the constitutional uncertainties the way they must have envisioned, by relying on reason, by respecting all the words the Framers wrote, by facing facts, and by seeking to understand their meaning for living people,” he said. “That is how a judge lives in a state of trust, and I know of no other way to make good on the aspirations that tell us who we are, and who we mean to be, as the people of the United States.”

Upon retiring, Souter returned full time to New Hampshire, and in addition to hearing cases on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit for more than a decade, he participated in civics education curriculum reform efforts in New Hampshire.

Souter returned to his alma mater multiple times to preside over the final round of Harvard Law School’s Ames Moot Court Competition, in 1991, 1993, 1998, 2000, 2005, and 2012. In characteristic style, Souter treated the student oralists to a genuine experience of what it was like to appear and argue before him in the U.S. Supreme Court.

During the 2012 competition, Souter was joined by Mark Wolf ’71 of the U.S. District Court for Massachusetts and Reena Raggi ’76 of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit, all three of whom had participated, on the losing side, in the final round of the Ames Competition while studying at Harvard Law. Empathizing with the students, Raggi recalled that her loss in the 1976 Ames finals had left her “convinced my life was over.” However, she reassured both teams that “there’s life after Ames, sometimes even on the federal bench.” Souter, who had competed in the 1966 competition, took a different lesson from his team’s loss. “I did not think my life’s prospects were coming to an end at all,” he told the audience. “I simply said, ‘I’ve got to find better judges.’”

Several current members of the Harvard Law faculty served as clerks for Souter during his tenure on the Court, including Feldman, Jeannie Suk Gersen ’02, and Rebecca Tushnet, who echoed the sentiments of many when she wrote: “I’m heartbroken.”

Tushnet, who clerked during the 1999-2000 term, recalled a lighthearted moment when at one oral argument Souter asked an advocate to say a little more about the “lore” on a particular topic. “Deeply confused back and forth ensued until the lawyer (and the rest of us) determined that this was how this unreconstructed New Englander pronounced ‘law,’” she said.

In a tribute in The New Yorker titled, “Justice David Souter was the antithesis of the present,” Suk Gersen wrote: “Justice Souter approached judging as a careful duty, not a vehicle for quotable soundbites or a run at a judicial Mount Rushmore. He inspired people who worked with him to extraordinary levels of affection and emulation that might well be inversely proportional to how vividly history will mark the impact of his jurisprudence.”

Feldman, who clerked for Souter during the 1998-1999 term, said working for the late justice was the privilege of a lifetime. “His kindness, his charm and his elegance of character were all palpable beneath the formidable facade of New England reserve. Sitting in his office exchanging ideas and stories with him, as the light faltered, I knew, as I have rarely known anything before or since, that I was in a chain of transmission that went back to the Puritan fathers who were his literal ancestors and my metaphorical ones. He was the best and wisest man I have ever known.”